Ulysses Journey 2022 In Context - Dr Stephen Graham

The text that follows contextualises the six films made as part of Ulysses Journey 2022 and draws connections between them. It describes some of their key elements and teases out some of the expected and perhaps more idiosyncratic ways in which they engage with Joyce, with the Joycean tradition more broadly speaking and with the capacious offerings of Ulysses itself.

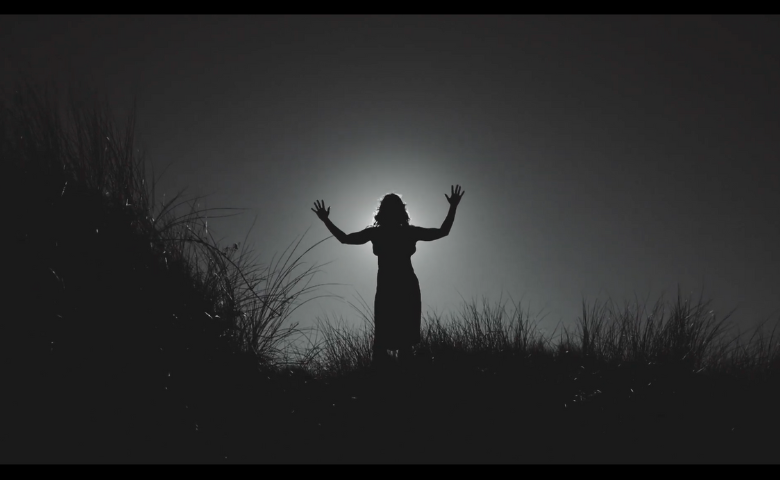

1. A woman stands on a sand dune with her back to us, hands and body eclipsing a shining moon in a blur of rain, ringing accordion and clacking electronics.

2. Huffing and wheezing accordion, loud and sharp, as a redded Penelope dances, gazes and ruminates her yeses and her AI garbles alike.

3. An accordion, and words, bubble, flow and boil as if water. Or do they?

4. Stephen, Joyce as clay, Angels of History, cluster accordion worrying at what it sees and tells before it collapses into light, exhausted of breath.

5. Grainy cine camera and busy, walloping music evoke the ‘ineluctable modality’ of Stephen’s audible walk on Sandymount Strand, via 1960s Mayo.

6. A spinning web of overlayed images and whirling clarinet, fiddle, concertina and voice frees us into the final Joycean yes, as an incubus – a prowling Eimear Walshe, standing in for life itself – presses down on our desiring, dreaming chests in the most intimate of clinches. Though it’s ‘not a sex thing’, not ‘exactly, not inwardly’.

These snapshots hopefully convey something of the spirit of these six remarkable films, all of them (bar one) featuring the accomplished, inimitable accordion of Dermot Dunne, and all of them likewise either playing with or pushing through and beyond the style, subjects and settings of Joyce’s Ulysses.

Already, indeed, you might have picked up on some Joycean themes and tropes in my brief descriptions.

This is not just in very concrete elements, like the reoccurrence across the films of Molly’s famous ‘yes’ or their use of other specific words, references and locations from the book. It’s also in their spirit and aesthetic style, which, like other musical works inspired by Joyce and Ulysses, from Berio’s Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958) and Sinfonia (1968-69) to Kate Bush’s ‘Flower of the Mountain’ (2011), inhabit an unmistakably Joycean space of allusion, sensual overwhelm and linguistic play.

Across each film here, after all, text and ideas that are either taken from or inspired directly by Ulysses are made to meld into or sing along with the artists and performers’ own fertile sounds, images and rhythms. This process of translation or transcoding honours Joyce’s own native artistic hybridity and prolixity; it’s indeed often been said of Joyce that he thought in and with music, that so many of his texts aspire in one or other way to the condition of music, whether it’s the famous fugal structure of the ‘Sirens’ episode of Ulysses or it’s the operatic allusions, form and feel of ‘The Dead’. According to Benjamin Poore, Ulysses itself ‘has hummed with sound for one hundred years’, with music providing many of its key images and reference points and also animating its prose in the form of neologisms and nonsense words. These films’ plays of musical text, textual music, and musically and textually animated image ultimately therefore serve as an extension and expansion of Joyce’s already cross-disciplinary music-artistic allusions, metaphors and techniques.

This plays out in different degrees and ways in each film, as we already started to see in the capsule descriptions with which I opened.

Luminary Reflection - Composer Ed Bennett and filmmaker Laura Sheeran, featuring Dermot Dunne (accordion), Thomas Bennett (spoken word), Ed Bennett (electronics), Stephanie Dufresne (dancer).

Ed Bennett and Laura Sheeran’s Luminary Reflection, for example, centres on a Bloomian monologue concerned with correspondences between heaven and earth, moon and woman. It plays musically with Joyce’s musicalized text and his conjoining and telescoping of the human with the celestial in its imagery. Such slippages of register and symbol are of course native to Joyce, but they also create further resonance beyond Joycean parameters here. Typically for Bennett—who in pieces like Song of the Books (2020), Psychedelia (2020) and Heavy Western (2018) seems to seek to reconcile both movement and stasis, trancing and balance, in sounds of great, concentrated energy—Luminary Reflection musically stages and enhances its given imagery, the sounds here slowly unwinding and building along the arc of the moon’s light as both reflections and refractions of that light, in sympathy with dancer Stephanie Dufresne’s poised performance.

Penelope - Composer Darragh Kelly and filmmaker Rioghnach Ní Ghrioghair, featuring Dermot Dunne (accordion), Hannah Mamalis (spoken word).

Darragh Kelly and Rioghnach Ní Ghrioghair’s Penelope pushes perhaps even further beyond Joycean themes and techniques. It launches off from the famous, almost ‘conjured’ sense and meaning of Molly Bloom’s closing soliloquy, rocketing up to a sort of ‘found’ sense and meaning related to its distinctive stream of artificial consciousness. Taking up Joyce’s mantle of an experimental and unregulated literary voice, which in the case of Molly delved inward in order to build outward, the film lenses this voice and this inner/outer play through Cagean or Burroughsian found expression and Holly Herndon-like cyborg artifice, with actress Hannah Mamalis evoking the weird duality of this play between the automated and the human. Crucially, as in Joyce, this stylistic boldness is anchored filmically here in richly embodied lived (female) experience, with Mamalis’ performance grounding the artifice in a clear emotional narrative arc from play to glory.

Luteofulvous Ebullition : the qualities of water - Composer Garth Knox and filmmaker Jonathan C. Creasy, featuring Dermot Dunne (accordion), Barry McGovern (spoken word), with water sounds by Garth Knox and Carol Robinson.

Garth Knox and Jonathan C. Creasy’s Luteofulvus Ebullition tries to encompass both Joycean virtuosity and Joycean intermediality or hybridity. The film is an encyclopaedic hymn to boiling water—the ‘ebullition’ of the title—that criss-crosses poetry and science, and textual and sonic analogy and free play, across a blistering and intense referential canvas of stretched and sensual words, rowdy facial expressions, and lithe, tense accordion sound. Music becomes water becomes music, via taut bellows and Barry McGovern’s skilled vocal cords and playfully authoritative performance. Though, as I said, it’s both analogous and free; this playfulness is crucial, since whilst it seems that we’re programmatically tied to water here the piece itself conjures many other, stranger impressions along the way too numerous and personal even to attempt to list. Just like Joyce’s wide ruminations on Bloom’s boiling kettle, the universe is in a drop of water here.

Pollen, Blood, and Seaspray - Composer Anselm McDonnell (with poetry by Euan Tait) and filmmakers Ross Wilson BEM, Art Ward, featuring Dermot Dunne (accordion), Nicole Rourke (spoken word), Anselm McDonnell (electronics).

Anselm McDonnell, Euan Tait, Ross Wilson and Art Ward’s Pollen, Blood, and Seaspray steps back from Joyce’s text, via Tait’s poetry, to inhabit a Joycean-eye-view of human history (Stephen’s line ‘History...is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake’ comes to mind), which is made manifest here in spraying sea and shore and full-bodied, acerbic accordion sonorities. This is one of those films that inhabits the spirit rather than just the strict word or letter of Joyce; as imagery moves wonderfully (and back and forth) from foamy seashore, to abstracted clay Joyce head, to Dublin house, and back to sea, McDonnell’s spare, moving, alert music undergirds a catharsis and metamorphosis, Stephen becomes ‘legend rain’ as we reach Joycean epiphany. Clarity following charged, sometimes opaque and thick, ratiocination.

I will see if I can see [Feicfidh mé má thig liom feicsin] - Composer filmmaker Ailís Ní Ríain, featuring Dermot Dunne (accordion), Jim Henry (archival recording provided with kind permission of the Henry family), Ailís Ni Ríain (prepared piano).

In I will see if I can see (Feicfidh mé má thig liom feicsin), by Ailís Ní Ríain, Stephen’s already near-audible mid-morning stroll on Sandymount Strand is rendered as vivid sound walk across Jim Henry’s 1960s County Mayo – the visuals are a collage constructed from Henry’s archival cine camera footage, and the spoken word Henry’s guttural, poignant Irish translation of segments from Ulysses. Mayo, specifically Doohoma, is treated like Guy Maddin’s Winnipeg and indeed Joyce’s Dublin here; both real place and site of immersive, musicalized imagination and fantasy. As with Ní Ríain’s previous work, in which immersive installations and plays feature alongside more conventional musical compositions, this piece blends image and sound, word and symbol, to create a universe of impressions, as ideas and fancies whizz by in hallucinatory, revelatory fashion.

cling(ing) like fire - Composer filmmaker Ultan O’Brien, featuring Ultan O’Brien (fiddle, viola and electronics), Eoghan Ó Ceannabháin (voice and concertina), Paul Roe (clarinet and bass clarinet), Camilla Houstoun (spoken word), Eimear Walshe (performer).

Ultan O’Brien’s cling(ing) like fire, finally, takes up Ní Ríain’s mantle of Joycean-inspired fantasy and runs to hell with it. In this spellbinding, scary, seductive work, which features the aforementioned Walshe as devil-incubus alongside humorous, mischievous musical (and otherwise) performances from Paul Roe (clarinet), O’Brien himself (fiddle, viola, electronics), Eoghan Ó Ceannabháin (voice and concertina) and Camilla Houston (spoken word), we are confronted with various Joycean Januses or suspensions; between waking and sleeping, suffering and healing, freedom and captivity, and hieratic, high-flown intellectual abstraction and the most primordial feelings, behaviours and experiences. These suspensions drive us into a kind of dazzled transcendence, an art-full, hyper-realised, liberation in which wild collisions of images and movement, nightmare symbols and musical effulgence, collage together beautifully to spin our heads in the most beautifully Joycean way. This film, the strangest and perhaps most seductive of the lot, is a suitable place to end.

So, as you will by now appreciate, each piece—in both sound and film, text and performance—lives in a rich Joycean world whilst also, in true Joycean spirit, pushing beyond given styles and stories to hint at new ways of creating with and in response to literature. These films and compositions can take their place in the grand tradition of artistic responses to Ulysses hinted at above, meeting Joyce in the strange artistic realm and lineage he conjured around himself but seeking, ultimately, to extend it and play with it.

- Dr Stephen Graham

Dr Stephen Graham is Head of Arts and Humanities, and Senior Lecturer in Music, at Goldsmiths. His book, Sounds of the Underground, came out in 2016. A co-authored book, Twentieth-Century Music in the West, just came out, and Becoming Noise Music will be published in 2023.