Through the Digital Door: works by Eric Sweeney in CMC's Library

This week's Through the Digital Door focuses on works by composer Eric Sweeney, who passed away on 21st July. He was a prolific composer, educator and organist, and he lodged over 140 works in CMC's Library. For this week's Through the Digital Door Library Co-ordinator Susan Brodigan takes a look through the library and archive at a small selection of his works. This week's feature also includes quotes from the composer from interviews in CMC's archive, including an interview from 'Musical Vistas', a 2004 programme on RTÉ Radio 1 and from interviews in CMC from 2004 and 2014.

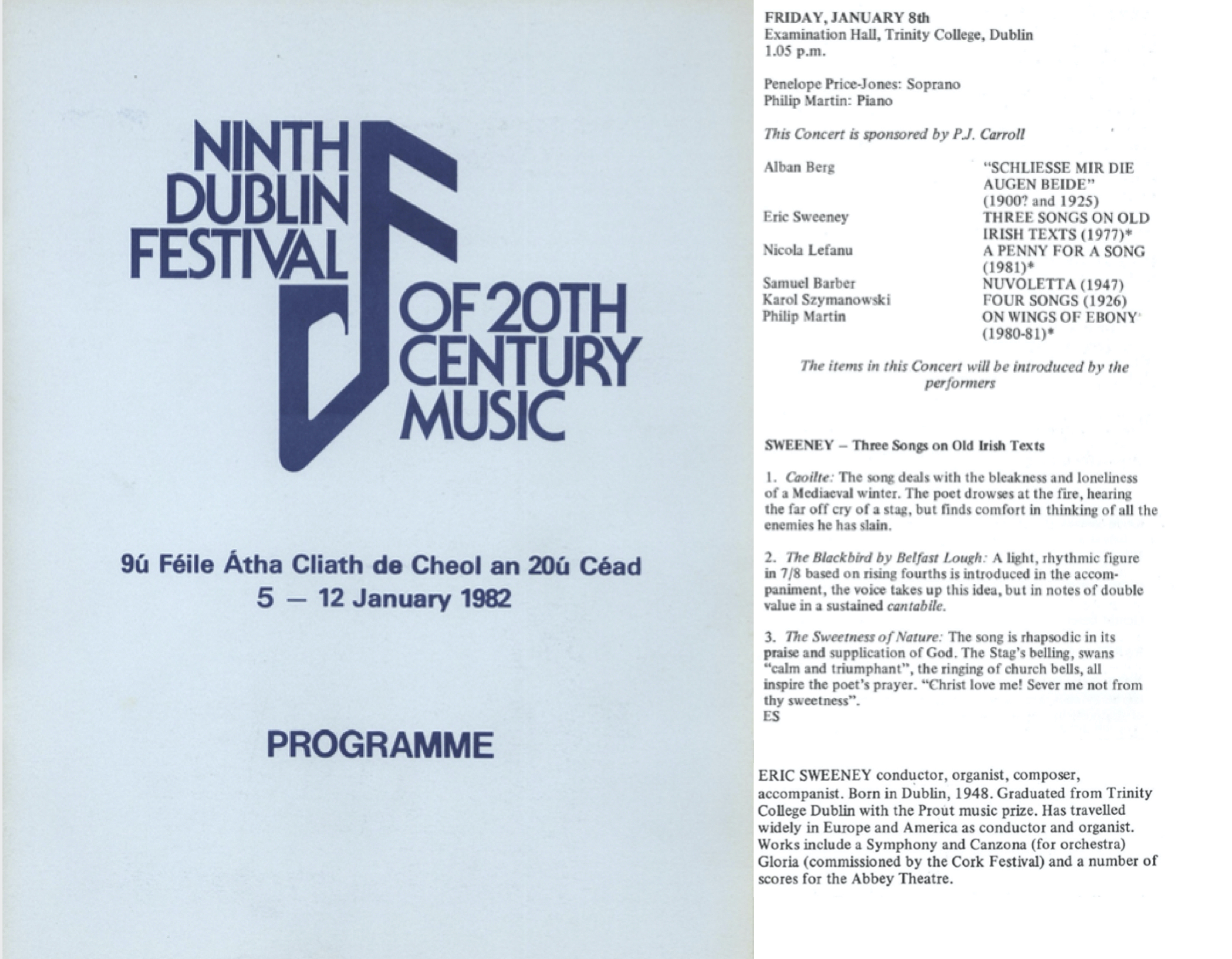

Three Songs on Old Irish Texts (1977) 6' for voice and piano

This work was premiered at the 1982 Dublin Festival of Twentieth Century Music in Trinity College Dublin by Penelope Price Jones (soprano) and Philip Martin (piano).

Eric Sweeney discussed his approach to composition on RTÉ Radio's 1 'Musical Vistas' in 2004:

It's hard to be objective about your music when I begin a piece. There's a delicate stage which you don't want to leave for too long or the ideas go cold. And yet, I don't want to rush it because I feel like writing in the white heat of inspiration, it worked for Schubert worked for Mozart, but I don't think it'll work for me, I like to begin a piece and then look at it from different angles. If I were a sculptor, I'd put it on a table, and I'd walk around it. And I'd come back to it. And I'd look at it from different angles, and I sometimes feel that I do with my music. And in a subconscious way, ideas come together and shape themselves.

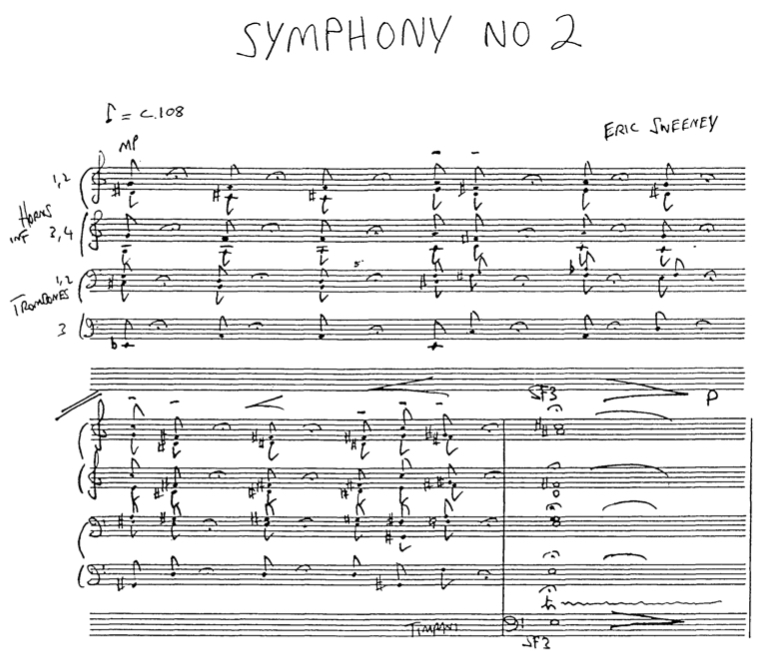

Symphony No. 2 (1985-1987) 22' for symphony orchestra

Eric Sweeney saw his Symphony No. 2 as a turning point. In an interview in 'Musical Vistas' on RTÉ Radio 1 in 2004 he discusses:

I see it [Symphony No. 2] as a turning point in my music. It begins in the earlier dissonant style, I'm playing around with aleatoric techniques, influenced by people like Lutoslawski. But then, in the last movement, although it is basically serial [...] it is also looking towards this new type of minimal music, where you start layering ideas, one on top of another, and you start expanding rhythms by additive process.

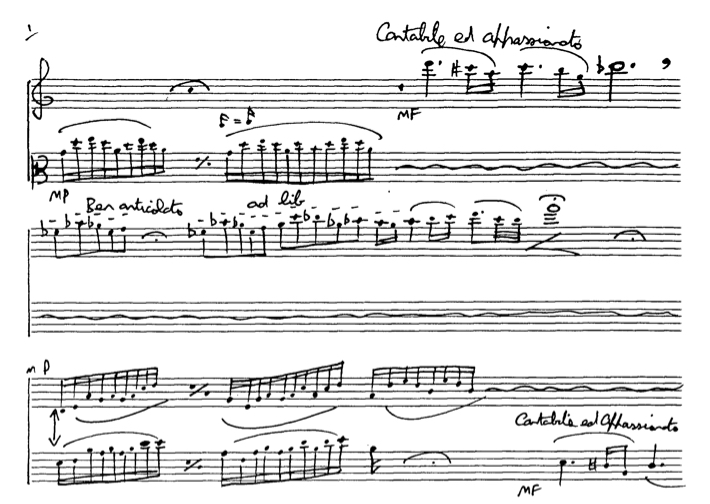

Strings in the Earth and Air (1988) 8' for violin and viola

This work was commissioned by Concorde with funds from the Arts Council and McCullough Piggott Ltd, and was premiered by Alan Smale (violin) and Elizabeth Csibi (viola) in the Hugh Lane Gallery. This work was written for the celebration of the Dublin Millenium 1988, and it was inspired by and related to James Joyce. The programme note with the work gives some more insight:

"Strings in the earth and air make music sweet; Strings by the river where the willows meet." Joyce's poem from the collection Chamber Music seemed to me an apt subject for a work to commemorate Dublin's Millennium. In the music, the opposing yet interlinked elements of earth and air are highlighted by contrasts of tempo, mood and dynamics between the violin and viola, which play at independent speeds with constant rubato for much of the time. Simultaneous speeding up and slowing down pass to and fro, and only at the risoluto is a constant pulse maintained.

Duo (1991) 4' for violin and piano

Originally written for violin and piano, this work was later rescored for a variety of instruments, including saxophone, bassoon, flute and clarinet. The work was first premiered by violinist Thérèse Timoney and Eric Sweeney on piano.

In an RTÉ Radio 1 interview, the composer discusses writing Duo:

When I wrote 'Duo' I was going through a period of trying to simplify my music. I think for a lot of people contemporary music seems quite complex. I wanted to make my message as simple as possible. The basic idea of the piece is just three notes [...] the challenge for the composer is how to make them interesting. The saxophone and the piano play various layers of rhythms, based on those three notes, more or less continuously throughout the piece. In the left hand of the piano part, I sometimes use a drone effect. The idea of the drone is from Irish traditional music, which was another interest of mine at the time. So the challenge was to take a very simple idea and see if I could create quite a complex piece.

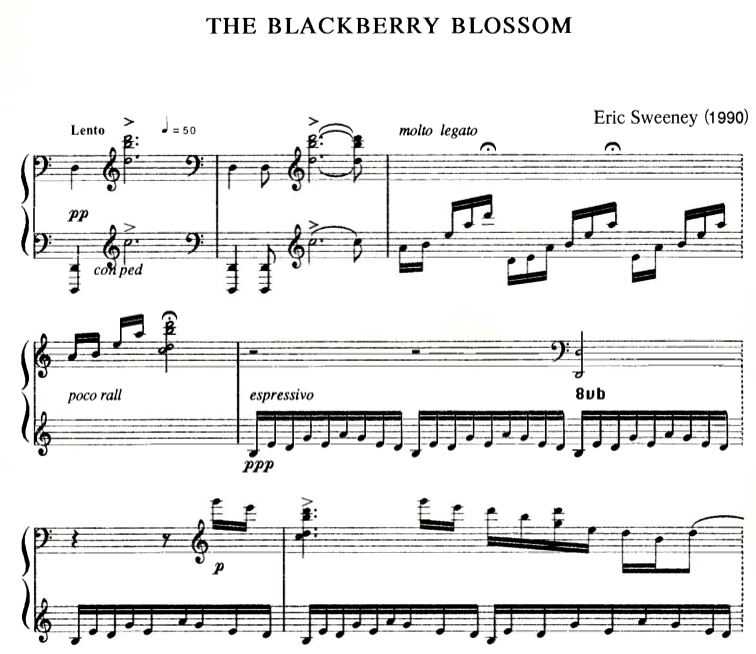

The Blackberry Blossom (1990) 5' for solo piano

This work was written in 1990 as a test piece for the 1991 GPA Dublin International Piano Competition. Pianist Enrico Pace won the IMRO prize for the best performance of a set piece that year with The Blackberry Blossom.

In a 2004 interview with CMC, the composer discussed the importance of being in touch with the performance side of music as a composer:

I think throughout history composers have generally been like that – think of Bach composing, performing on several instruments, conducting choirs and doing administration. It's also a great way of keeping your feet on the ground because if you write something for performers that doesn't work, they'll soon tell you. As a teacher, it's advice I give time and time again to young composers: get your music out there, go and badger a few friends into playing your music – it's a huge learning experience. One of the problems with music technology is that you can do a score in Finale or Sibelius and you get a midi performance straight away. The computer isn't going to tell you 'no, this register is not going to work for the clarinet,' – computers don't complain. It's immediately obvious [to me] looking at student works if someone has gone through the process of working with performers – it's by far the best way for any composer to learn the craft.

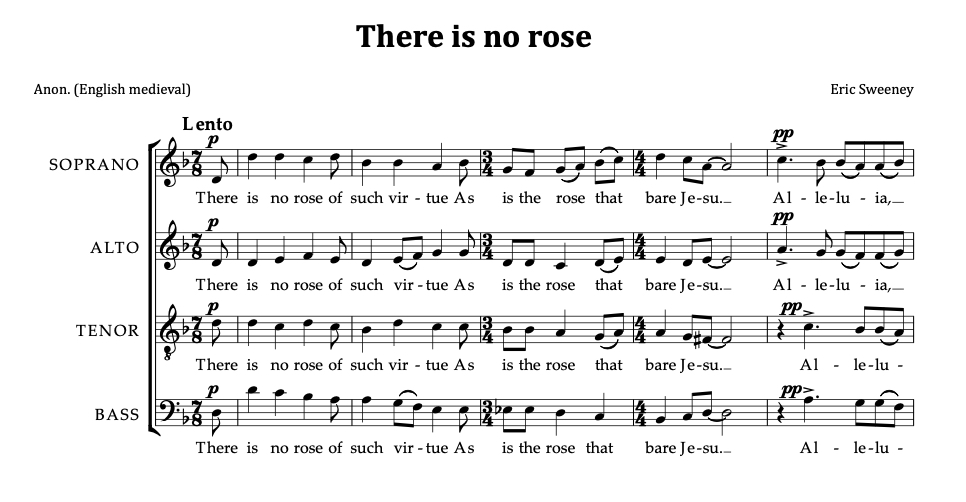

There is no rose (1991) 3' for SATB choir

This work was premiered by Waterford College Choir in December 1989. It is included in Choirland, a collection of fifteen works for unaccompanied mixed choir by composers from Ireland. This collection includes recordings of each work by the National Chamber Choir of Ireland, conducted by Paul Hillier. The composer discussed composing choral music on RTÉ's 'Musical Vistas':

Having grown up with the choral tradition, from a choirboy, and in all my musical working life, I have always worked with choirs. As a composer, it would be strange if I didn't write for choirs. Dissonance, that clash of one note against another, is completely transformed if you write for voices. To write gratefully for voices is a particular challenge for composers. I hope I have done that; I hope my music is grateful to sing. I don't think it is particularly easy: I'm not sure why this should be. I don't sit down to write a difficult piece of music: it's the way it turns out. As a composer, you're searching for a certain sonority that hasn't been done to death before. I hope I have attained that to some degree in this little carol 'There is no rose'.

It has a lot of dissonance [...] caused by the clash between voice and another. The element of dissonance is one of the reasons a lot of people don't like modern music [...] but, of course, it is a relative term. It is the spice in music, and, in the same way in food, if you took out any seasoning it would taste very bland, the same in music. It would be impossible to imagine a successful piece of music without dissonance.

The Secret Rose (2002) 4' for solo organ

This work was written in 2002 and premiered in St Michael's Church in Dun Laoghaire in June 2003 by the composer. The programme note provides some background:

The Secret Rose is one of a series of short pieces based on poems by Yeats, although there is no direct programme element in the music. Simple chord patterns move in contrary motion throughout the piece, only reaching a resolution at the cadence.

Eric Sweeney discussed his musical influences with CMC's Jonathan Grimes in 2004:

I find I'm influenced by a huge number of composers. It's not just the contemporary ones who have shaped my own compositions – I'm influenced by the whole canon of music. Of the twentieth-century composers, Stravinsky, Bartok and Messiaen are the composers who have influenced me most. I listen to a wide range of music, and it's difficult to be objective about it because composers just reflect what they hear. I greatly admire Louis Andriessen for the sheer energy and raw qualities of his music. A lot of the American minimalist composers I find boring. What attracts me to so much of that music are the ideas behind it: this new way of looking at music – it is this, more than the actual music, I find exciting.

The Invader (2013) 84' chamber opera

This work was premiered in 2014 in the Theatre Royal in Waterford. The libretto was written by Mark Roper, and the performance was directed by Ben Barnes. Here Eric Sweeney spoke with CMC about the background and story of his opera:

The origins of it [The Invader] was in a project I did in 2011 in Waterford for the Tall Ships Festival – there was a pairing of composers with poets. Each were to compose a movement, and it was performed in the open air down at the quayside with massed choir and orchestra [...] I happened to be paired with the poet Mark Roper, and we got on well, and the piece was a success. We then talked about doing some other projects together.

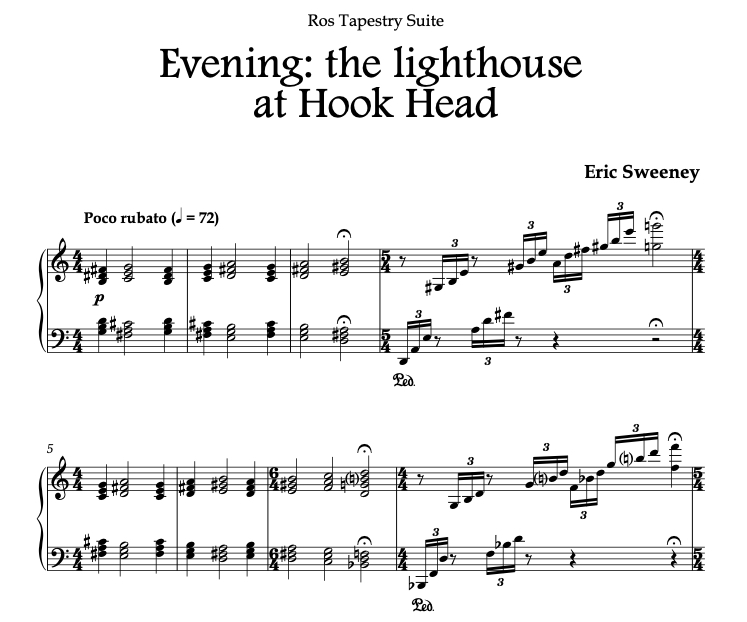

Evening: the lighthouse at Hook Head (2015) 5' for solo piano

This piece is the sixth work in the Ros Tapestry Suite, which was written in 2015 and commissioned by the New Ross Piano Festival. The work was premiered at the festival in St Mary's Church by Olga Scheps.

In his interview on RTÉ Radio 1's 'Musical Vistas' in 2004, Eric Sweeney discussed the importance of music:

I think, in another existence, what I would really like to be is a medical doctor. I sometimes think it's marvellous to be a musician, but I'm not really of any great use to anyone. To be able to heal people, it seems something very special in life, to make people well. When I say my music is of no use, I hope it is of some. It won't make anyone better, but [...] music does heal. Music is a very important part and has to do with quality of life. It's to do with the soul, and it's impossible to quantify that.