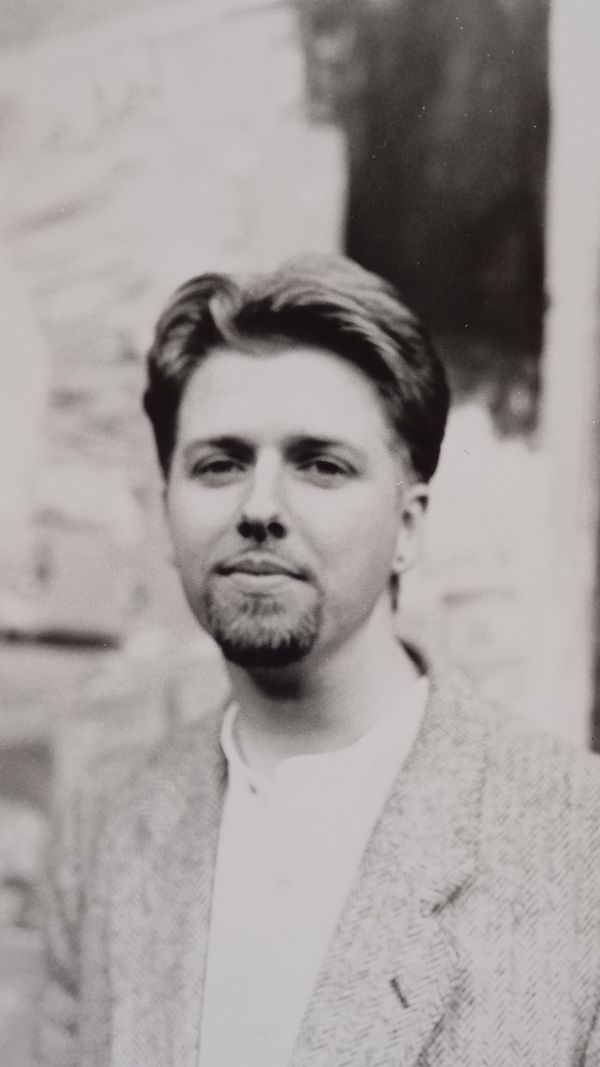

Seizing the day: Ian Wilson at 60

‘Seizing the Day: Ian Wilson at 60’ was commissioned by the Contemporary Music Centre on the occasion of the composer's 60th birthday. Written by Tim Rutherford-Johnson, it is printed in a limited edition of 200, available to order from the CMC Shop. Printed copies are free of charge (excluding price of postage).

Photo credit: Méabh Noonan

‘The biggest challenge was writing something up to the level I felt it needed to be for these particular players’. I’m sitting with Ian Wilson in the downstairs dining room of his holiday home in Belgrade, where he is talking me through the background to Orpheus Down, his fifty-minute duo for bass clarinettist Gareth Davis and double bassist Dario Calderone. We’re on the outskirts of the city: the streets are still tightly packed with homes, but the roads have the narrowness of rural tracks. Every trip out is a pavement-less, hair-raising adventure. The house is light and spacious with a robust Art Deco-ish style to its furniture and fittings. There’s a top floor that needs finishing, and when here (he divides his time between Cavan and Belgrade) Wilson, his wife the violinist Dušica Mladenović and their young son live on the middle floor. Ian himself seems to thrive on the buzz of a city that still plays by its own rules.

‘When the occasion presents itself, I try to seize the opportunity to really push myself, compositionally’, he continues, searching his laptop for a video to show me what he means. It takes a little while because he is a prolific composer: a directory of materials related to each of his compositions contains more than two hundred subfolders. ‘I felt [Orpheus Down] was doing this in terms of the actual material’, he says as he scrolls, ‘But also in terms of the inspiration and in terms of the structural challenges – if you’re going to write something forty-five, fifty minutes long then it needs to feel that it needs to be that long. But also that it doesn’t necessarily feel that long.’

Eventually, he finds the video and pulls it up. Davis and Calderone are alone in a rehearsal studio, filmed by what I presume is a phone propped up on a music stand. The atmosphere is relaxed: other music stands are dotted around the background, as well as the players’ open instrument cases. But when they begin to play – dense, jagged gestures, both amorphous and tightly sprung – the concentration is absolute. And the sound is startling. My own memory of Ian’s music is of something more melodically and harmonically driven, something closer to the musical mainstream. This has a different kind of snap and energy. As I watch and listen, I wonder: what chain of opportunities led us here?

I’ve interviewed Ian Wilson once before, long ago. Back then, I was fresh from my studies and had been invited to write an article for the British journal Tempo. He was riding the crest of a rapid start to his career, with election to Aosdána (Ireland’s national association of creative artists), a commission from the BBC Proms and a major publishing contract with Universal Edition already under his belt. I knew nothing about him or his music beyond such scant biographical details, but I was young enough to relish the challenge, and so I said yes. When I wrote to Ian, he said he would be in London soon and suggested we meet at an Italian restaurant in the centre of town. Over plates of pasta, he told me about his concertos for piano and violin, Limena and an angel serves a small breakfast; his Fourth, Fifth and Sixth String Quartets; and his opera Hamelin, written with the poet Lavinia Greenlaw. I’d done my homework with CDs and scores sent to me by his publisher, but this being my first ever interview, I found it nerve-wracking keeping up with Ian’s knowledge of both new music and twentieth-century art (Paul Klee came up a lot, I remember). Still, we bonded over a shared love of the late, slow works of Luigi Nono, music I had only recently discovered, and he was generous with his time and words and did everything he could to put me at ease. If he was worried he was entrusting himself to a know-nothing beginner, he didn’t let it show.

Photo credit: Ian Joyce

The article that came out of that meeting – ‘Out of Belfast and Belgrade: Ian Wilson’s recent music’ – was published in April 2003 and became the first item on my CV as a professional writer. The second came shortly afterwards when Ian put me in touch with the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna – where his Fourth Quartet, Veer, was being performed by the Artis Quartet – to contribute a short feature for their subscriber magazine. Over the next few years, I honed my craft across several sleevenotes for Ian’s music as his profile across Ireland and Europe grew.

While I welcomed Ian’s support at the start of my career, I also appreciated the chance to watch the evolution of a still-maturing artist. In 2003, I had identified a stylistic rupture around 1998–9, when Wilson had moved briefly to Belgrade (his then-wife, the late musicologist Danijela Kulezić-Wilson, was Serbian) before being forced abruptly back to Ireland by NATO’s bombing of the city in March 1999. Up to that point, Wilson had been writing music in a florid lyrical style, exemplified by Limena and an angel, concertos in which the orchestral accompaniment is comprised almost exclusively of notes played by the solo instrument, either sustained, delayed or anticipated, to create a resonant, ever-shifting halo of sound. After 1999, his music understandably took a darker turn, as in his Fifth Quartet, … wander darkling and Abyssal for bass clarinet and chamber ensemble (both 2000). These works are more aphoristic, their structure comprised of short, disjunct episodes rather than long, unfurling melodies. They also place an emphasis on extended playing techniques, particularly the Fifth Quartet, with its susurrating drones and harmonics that skirl like sand martins over a darkening sea. Part of this was a deliberate turn towards new compositional territory, but part of it, as Wilson told me back then, was fostered by his anger at both the ‘little Hitlers’ like Slobodan Milošević and the ‘big bullies’ like NATO and his sense of loss for a city that he loved.

As it turned out, this change in direction was also only temporary. It led to some of the best music of Wilson’s career – pieces like the ethereal, fidgety, plunging Sixth Quartet In fretta in vento, and the malevolently reverberating Licht/ung for orchestra. Ian continued sending me CDs through the noughties, but towards the end of the decade, the ones I received had me rethinking what he was about as an artist. Two stood out in particular: TUNDRA, a forty-minute cycle for trumpet and electronics, and Double Trio, a suite of pieces for three jazz and three classical musicians. As its title suggested, TUNDRA was a windswept vista of electronic echoes and lonely trumpets. Double Trio, meanwhile, drew on Steve Reich’s trick of extracting melodic material from spoken recordings, using interviews with residents of Glencullen in Dun Laoghaire to give the music a bouncy, almost cabaret-esque feel. The two discs were utterly unlike each other and unlike anything of Ian’s I knew up to that point.

Written biography is only a snapshot in time, and change is an artist’s prerogative. More than once, I’ve published an overview of an artist, only for them to do something contradictory almost straight away. Yet I found Wilson’s new trajectories especially unexpected: I thought I’d seen in his work a strong stylistic identity, and although works like the Fifth Quartet substituted episodic form for that vapour-trail melodicism, in the Sixth Quartet and the marimba concerto Inquieto, I believed Wilson was continuing to explore and consolidate his musical language. What was going on with these new pieces, then?

Today, Wilson identifies 2007 as the turning point. And the trigger was a player: the saxophonist Cathal Roche. The two musicians had known each other for a while before this. They lived close to one another in Leitrim, and Roche’s Rise Saxophone Quartet had played Wilson’s early work so softly. Yet it was a couple of years before Wilson decided to write the saxophonist a piece. In 2006, after playing Wilson’s Spilliaert’s Beach, Roche invited the composer to hear him in Dublin with the Kai Big Band. It was the first time Wilson had heard him improvise. ‘I was really knocked out by his playing’, he says now, ‘because he was doing all those interesting things – circular breathing, microtones, lots of interesting textures’. Straight after the show, he told Roche he would like to write him a piece: something that would allow him to play like that, but in a context of Wilson’s devising. Once the Vanbrugh Quartet were on board, as well as pianist Hugh Tinney and bassist Malachy Robinson, Wilson set to work on re:play, a septet for classical and jazz instruments. Inspired by Samuel Beckett’s Play, the work takes its basic melodic material from transcriptions of the opening speeches of each character in Anthony Minghella’s film of that work. Again, there is an anticipation of the Double Trio, although the overall mood here is darker, nervier, reflecting the highly stylised speech patterns of Beckett’s characters.

The classical/jazz combination extends not only to re:play’s instrumentation but also to its compositional technique. About a quarter of the saxophone part is improvised, either with Roche working within a fixed period or extemporising at his own pace while the ensemble loops accompaniment figures beneath him. There are hints of the ‘controlled aleatory’ of Polish composer Witold Lutosławski, as well as the cool jazz of a Lee Konitz. Classically for a transitional work, it’s not quite one thing or another, and the edges between are not quite as smooth as they might be. Yet, while the jazzy elements are kept on a tight leash, they add a distinctly different melodic, rhythmic and timbral palette that one can hear reverberating through Wilson’s music for another decade or more. A recording of re:play was released on the Riverrun Records CD In shadows in 2011. I wrote the sleevenotes, and even now, you can see the difficulty I had in reconciling its boppy vibes with the CD’s title and the two other works on the disc – the 9/11 elegy Across a clear blue sky and the murky hall of mirrors im Schatten. In the end, I resorted to describing the Beckett transcriptions as ‘re:play’s shadow’ for how they ‘darken the language of the whole’. An unsatisfying resolution, perhaps, but in retrospect, its awkwardness speaks to something that was taking place more deeply in Wilson’s music.

Today, Wilson gathers the various paths that his music took through the late 2000s and 2010s under the heading everythingism. It is a word he picked up in 2019 from an exhibition at London’s Tate Modern Gallery of the work of the Russian artist Natalia Goncharova. (The original term, vsechesvto in Russian, was coined by Goncharova’s partner Mikhail Larionov and the writer and artist Ilia Zdanevich.) It refers to Goncharova’s determination not to be artistically limited by stylistic pigeon-holing and the diversity of her work – in painting, printing, theatre design, film, performance art, illustration and fashion. Wilson says the description was a ‘lightbulb moment’ for him. He had always been an eclectic listener, with tastes running from bebop to heavy metal. As these influences began to seep into his music, everythingism permitted him to feel validated engaging with a variety of musical styles and contexts.

After the jazz-inspired re:play, Double Trio and The Book of Ways (for saxophone and improvising string quartet), the next manifestation of this was an engagement with Irish folk music. In 2009, an 18-month post-doctoral research position became available at the Dundalk Institute of Technology. The post had arisen fortuitously – someone had dropped out, and Wilson successfully applied to take their place. The only stipulation was that Wilson’s research had to be related to Irish folk music and technology. Although neither was especially his area, in the spirit of seizing opportunities when they arise, Wilson gladly agreed. He was put in touch with a young sean-nós singer, Lorcán Mac Mathúna, as well as a lecturer and programmer at the Institute, Rory Walsh. Using a bespoke software system created by Walsh that captured sounds so that they could be looped or their different tones sustained, Wilson set about investigating the compositional possibilities of combining sean-nós ornamentation with these looping/suspended sounds. Roche was brought in as a complement, and in the unique line-up of sean-nós singing, improvising saxophone and live electronics, the trio performed as Common Tongue and released an album, want & longing, on Nippi/Psychonavigation Records, in 2010. The eight tracks on the album are based on traditional lyrics, but the melodies are all Wilson’s own. He would write these melodies ‘clean’ before giving them to Mac Mathúna to sing in his own way. This made it easy to then separate the ornamentations as generative compositional materials. The result is a unique record: ancient and earthy, but also sensitive to sean-nós as a living tradition, Roche and Wilson’s contemporary timbres echoing the shadows and glimmers of Mac Mathúna’s singing.

The effects carried over into Wilson’s concert pieces. His Twelfth Quartet Her charms invited, for example, is marked by a densely florid melodic style that owes much to sean-nós. Two more pieces were written in a similar fashion: Where the moorcocks crow for alto saxophone and saxophone quartet, and The linnet sings her note so pleasing for quartertone bass flute and electronics. All three are based on the same melody Wilson wrote to the old Irish song ‘The mountain streams’ – also the basis of the first track on want & longing. These works might form a distinct subgrouping of Wilson’s overall output, but how these essentially monodic pieces use imitation and outspilling ornamentation to create harmony from a single line has distinct echoes with his late 1990s ‘vapour-trail’ works.

In 2003, Wilson took up a position as director of the Sligo New Music Festival. Although he had found the role personally satisfying, and the festival had had some successes (he highlights events featuring Gavin Bryars, the music of Nono and Feldman, and the Australian musicians Genevieve Lacey and Oren Ambarchi), by 2011 he felt he had taken the festival as far as he could. To mark his last festival, he and Roche performed as a duo under the name crOw. Initially intended as a one-off, the partnership was revived for ‘Sounding the City’, a project for the 2015 Cork Midsummer Festival that involved responding musically to various buildings around the city. Playing in the National Sculpture Gallery, the giant City Hall atrium, Diarmuid Gavin’s Sky Garden pod in Fitzgerald Park and the trendy Gulpd café (formerly part of the Triskel Arts Centre), Wilson and Roche created a portrait of the city’s different acoustic spaces.

The previous year, crOw collaborated for the first time with one of Ireland’s leading experimental groups, The Quiet Club of Danny McCarthy and Mick O’Shea. Wilson had been aware of the duo since moving to the city, and in 2014 invited them to take part in his experimental, improvised opera The Last Siren. That work premiered at the Theatre Development Centre, Triskel in Cork, and then in 2015 went on tour to Ireland, Northern Ireland and Scotland. Its last performance was due to take place at Sligo on 6 December, but storms prevented the singer – Lauren Kinsella – from flying to the planned rehearsal the day before. Having driven across the country through floods and bad weather themselves, Wilson, McCarthy and O’Shea opted to make the most of an unexpectedly free evening. Securing some studio time at The Model in Sligo, as well as the help of sound engineers Ray Duffy and Patrick Curley, they invited Roche (who lived nearby) to join them for a jam. The result was a thirty-minute live album, As the quiet crow flies, released on farpoint recordings in 2016. (An expanded version, with an additional session recorded at Library House, Dean Street, Dublin, was released in 2022.)

Photo credit: Jed Niezgoda

As its name suggests, As the quiet crow flies is an album on the edge of silence: McCarthy and O’Shea contribute crackling textures, electronics and sound objects, while Roche reduces his saxophone to muted groans and squeaks. Wilson – who plays electric guitar, toys and e-bow (a magnetic device that makes strings vibrate without having to pluck them) – says that for all its accidental origins, the experience transformed his own improvisational practice. ‘That turned out to be a really beautiful experience from my point of view’, he says in an interview given to the Contemporary Music Centre, Ireland around the album’s original release. ‘When I’m playing with Cathal, we can be quite full-on in terms of the sound we make, and yet obviously, by the nature of what they do, The Quiet Club have a much more nuanced and subtle approach to making sound. … The experience of Cathal and I playing with them was very different for me. I found myself listening a lot more and playing a lot less than I would if it was just the two of us. There was a lot more space to get involved with, a lot more silence. Even in that hour, hour and a half that we played together, I felt that I had learnt so much.’

Of course, alongside these excursions into folk music, electronics and improvisation, Wilson was continuing to write ‘straight’ concert music. And there was no less variety in his work here. Examples are too many to mention, but highlights include Stations (2006–7), an austere solo piano meditation on the Stations of the Cross; the abrasively motoric alto saxophone concerto Sarée in Kassel (2009); and the ambitious Yeats setting, Slouching Towards Bethlehem for choir (2015). A residency with the Ulster Orchestra in 2011–14 produced three symphonic works, and engagements with public arts programmes led to substantial pieces like Still life in green and red (2011) for string quartet and soundtrack, written for Mayo County Council’s ‘Landmarks’ programme.

One further thread was an enduring relationship with the Adelaide and Meath Hospital in Tallaght, Dublin (now known as Tallaght University Hospital). This began in autumn 2010, when Wilson held a ten-week position as Composer-in-Residence at the hospital’s stroke unit. During this time, he, soprano Deirdre Moynihan and members of the Irish Chamber Orchestra visited the hospital every two weeks to give a concert of light classical music, and to present extracts from the song cycle Bewitched that Wilson was composing, based on conversations with stroke sufferers and healthcare workers about their experiences of the condition. The response of patients to the postwar light music they listened to during their physiotherapy sessions inspired Wilson to combine each of his settings of patient interviews with a song by Doris Day. The idea was for each to provide a commentary on the other, but the juxtapositions (always surprising but never jarring) demonstrate as clearly as anything Wilson’s continual desire to use technical challenges as musical inspiration.

‘A lot of these 250 pieces are about trying to have a compositional experience, which results in a piece of music. And some of them are successful, and some of them aren’t.’ Back at the table in Belgrade, Wilson is musing on his artistic identity. ‘It’s probably less disorienting for me than for other people. I’m interested in so much stuff; I suppose this is just a reflection of what I like to listen to. Not in terms of trying to recreate it but just in terms of the sheer variety. I never felt that I needed or wanted to settle in either style or voice, particularly.’ He is proud of the work he produced in that everythingist decade after 2007, but he is also aware, I think, that the pursuit of opportunity can lead to a certain eclecticism. ‘I think I was, even unconsciously, looking for something to hold onto. Trying to find something again. It’s only when you get to 2018 where I’m starting to explore’, he pauses, ‘ … absence.’

Wilson has long been interested in voids and empty spaces as musical inspirations – as seen in works such as Abyssal, Cassini Void (2007) for clarinet and ten instruments, or even TUNDRA – but they come to the fore in an important work of 2018, The emptiness of the ever-expanding universe cannot compare to the void where your heart should be. Commissioned and premiered by Belfast’s Hard Rain Soloist Ensemble, it is a rare political work within Wilson’s output. Dedicated to ‘so-called leaders and people in power everywhere who pander to their own desires, dogmas, pockets, narrow support bases, and/or stockholders instead of the greater good’, it attempts to portray the vacuity of political promises through music of deliberately meagre means. Written for alto flute, bass clarinet, piano, violin and cello, plus various auxiliary objects, the music is often reduced to little more than the scattered pings of a music box or the hiss of radio static. Even when they play, the instruments produce broken, dislocated sounds: the tap of a bow on a string, the toneless hiss of air through a tube. ‘I was trying to create something like: what would music sound like if there was no real music there?’ Wilson explains. The result is dry but never flat: interest comes from the intensity of each sound as it is introduced into the space, and the fragile web of connections and contrasts that is strung between them.

Three years later, absences took on a more personal resonance in Beside the Sea (2021), a major work of instrumental music theatre. (Wilson first explored the idea of wordless theatre in 2009’s Una Santa Oscura, inspired by the life and work of Hildegard of Bingen.) Beside the Sea was written following the death in 2018 of Wilson’s father Jim after a long battle with Alzheimer’s, and it explores the themes of loss and memory that this implies. An electronic soundtrack (made in collaboration with composer Steve McCourt) incorporates sounds of Jim’s beloved ocean, his tools, his guitar, the choir he sang in for forty years and, most poignantly, a rediscovered recording of his wife, Norma, a professional soprano and the last voice he was able to recognise. Although it resonates with grief and loss – the relentless passage of Alzheimer’s is reflected in the music’s gradual disintegration over 50 minutes – Beside the Sea is also a portrait of love. Wilson tells me later, over email, that making it helped him deepen his appreciation and understanding of his father.

As he continues to talk to me in Belgrade about his new artistic focus, Wilson tells me how his resurgent exploration of images of absence runs alongside his ongoing love of deep instruments. I have a flashback to our first meeting.

‘It’s late Nono again!’ I joke.

‘Maybe!’ he laughs. ‘His music is very inspirational. You listen to pieces like Post-Praeludium per Donau, he continues, referring to the Italian composer’s 1987 solo for tuba and electronics, an astonishing tapestry of hushed moans and growls produced deep within that cavernous instrument. ‘It occupies a space that I think a lot of music wants to occupy these days but doesn’t. Because there’s something about absence in music that’s very hard to catch, musically. I think you have to be a certain age to be thinking about absence in music. Because it’s bound up with loss as well as philosophy.’

And then he pulls himself up. ‘Maybe that’s bollocks, Tim. But it feels right to describe it like that.’

Perhaps. But as the example of Nono suggests and both Beside the Sea and The emptiness demonstrate, absence can be a positive musical attribute, inspiring attention, delicacy and intimacy. Recent pieces like these surely build on Wilson’s experiences playing with The Quiet Club – particularly that first, revelatory session in Sligo at the end of 2015. Also personally and artistically important has been his relationship with Mladenović, which developed over roughly the same period. As the sole performer of Beside the Sea, for example, she played an essential creative role (alongside director Olivia Songer and designer Jack Scullion) in developing the work’s look and feel – ‘her performances (acting- as well as performing-wise) will hardly be bettered’, he says. And she has become his most important collaborator; he has written more for her in the last few years than for any other musician, even Roche.

One of those pieces is I Quattro Elementi for solo violin (2020). Each of its four movements is confined to a single string – G, A, E, D – and the character of each string is paired with one of the four classical elements: earth, water, fire, air. Wilson worked closely with Mladenović in researching the sonic possibilities and implications of restricting each movement in this way. In addition, the first movement, with its wide arpeggios up and down the G-string, is inspired by a warm-up exercise he heard her playing one morning. The third movement is relatively conventional in its fiery top-string passion. But it is in the second and fourth movements (the latter in particular) where Wilson feels he was taking a greater leap. The second resembles one of the ‘postcard pieces’ of the American experimentalist James Tenney in its articulation of a single, wave-like gesture – in this case, the slow oscillation of a tremolo between a point behind the bridge and the fingerboard. And that’s it. The fourth begins and ends with circular bowing motions that apply a minimum amount of bow pressure to produce a breath-like sound and rhythm. An abstract ‘dance’ of quaver harmonics, followed by a slow, lyrical melody, provides a contrasting middle section.

I Quattro Elementi was soon followed by TOTEMIC, for viola and percussion. In the earlier piece, Wilson had found a new comfort with presenting his musical materials completely unadorned, discovering that they could have enough interest and enough of a trajectory on their own. Now with the viola, he was keen to explore a similar approach on a deeper, more resonant instrument. TOTEMIC responds to Luciano Berio’s Naturale, for viola, percussion and soundtrack, which draws on field recordings of the Sicilian street vendor Peppino Celano as inspiration. Wilson turned once more to Irish folk music, and the melody he wrote for ‘The mountain streams’. But whereas that melody in 2009 was a staging post for explorations of ornamentation and embellishment, ten years later, Wilson uses it in only bare fragments, setting the hushed timbres of his later piece in stark relief. To some extent, these fragments prevent the work’s fragile textures from blowing away entirely, but at the same time they are, in their naked simplicity, symbolic of a different kind of absence, casting the brushed percussion and scraped strings that surround them as the work’s real centre of gravity.

Photo credit: Marko Djokovic

I describe those passages as hushed, but quietness in this case is less a matter of decibels than a way of playing. All instruments, when played extremely quietly, produce completely different sounds than they would normally: bows crackle and pop when they run across a string, for example; air in a wind instrument escapes in unexpected ways. One of the discoveries of I Quattro Elementi was how much structural potential there is in that contrast. While recording TOTEMIC (for the Ergodos label), Wilson further observed that if you then mic and amplify those sounds, you get music that isn’t necessarily quiet in terms of volume but is in terms of feeling. ‘It’s the whole notion of piano’, he explains. ‘It’s soft, rather than [an] actual dynamic.’ Much of the writing of TOTEMIC has the delicacy and tension of music played at the limits of audibility, even if the resulting sound is, in practice, much louder.

Loss, of the sort that only comes from the passing of time, plays its part in this piece, too. As Wilson was completing it, Kulezić-Wilson, by then his ex-wife, passed away. As a tribute to this ‘unique person in my life’, he incorporated fragments from his 1996 piano solo, A Haunted Heart, a work he had written for her before their relationship began. Even more than the fragments of ‘The mountain streams’, these are moments of apparent solidity and security; even more, they are only shadows, a way to articulate an absence from out of a presence.

The ongoing love of low instruments represented in Orpheus Down, meanwhile, can be traced back to 2000’s Abyssal. That work represents an early foray into the sorts of extended techniques that are such a feature of more recent pieces – quartertones are used extensively, for example, to capture the strangeness of a deep-sea environment (although the work equally takes inspiration from Jackson Pollock’s 1953 painting, The Deep). It also features an unusual line-up of flute, clarinet, steel-string guitar, harp, violin and double bass that was to be a dry run for the ensemble used in Hamelin. (It is an under-remarked quality of Wilson’s output that years of writing to commission have given him great facility with every imaginable instrumental combination.)

Abyssal has a recent counterpart in Marianas for Sarah Watts’ solo contrabass clarinet, flute(s), violin and piano; other recent works with a low-end emphasis include Wild Is the Wind for bass clarinet (a gorgeous deconstruction for Davis of Nina Simone’s rendering of the eponymous song) and we have no prairies, an extended work for contrabass flute, contra-alto clarinet and soundtrack that Ian was working on when I visited. But Orpheus Down is the biggest of these works. Given its need to respond to an existing story – Orpheus’s descent into the underworld and his final loss of Eurydice – with its own structure and emotional contours, the musical language is less concerned with absence than some other recent pieces. Instead, the music takes those improvised snippets Wilson had shown me videos of and transmutes them into an evocative aural picture of Orpheus’s journey: the falling rain, the creak of Charon’s oar, the descent into Hades … As in TOTEMIC, the music is mostly built from unconventional sounds (a kind of arpeggiation between the two instruments that sounds spookily like a dying fairground organ being the most remarkable), but again it is threaded with snatches of melody that impart light and shade, and that personify Orpheus as he makes his way down.

Wilson views Orpheus Down as one of his most important recent pieces – thanks again, he acknowledges, to the inspiration provided by the two players for whom it was written. But another work draws together more of the past and future threads of his music. This is Voces amissae (Lost Voices), a kind of song cycle for voice, cello, three violas and two percussionists. Wilson’s original plan was to write a piece for the Dutch soprano Nora Fischer, but when he approached her in 2022, she told him that she was having difficulties with her voice and was at that time unable to sing. She still wanted to be involved, however, and so the idea of ‘lost voices’ emerged as a theme. As a textual basis for the work, the two musicians began collecting quotations from and interviewing people who had lost their voices in one way or another: Fischer focused on people whose voices had been suppressed politically, or through violence or homelessness; Wilson, partly drawing on his contacts at Tallaght University Hospital, with those who had lost their voices for medical reasons. These included a young woman who had had a post-partum stroke; an older lady with motor neurone disease; and the English singer Sheila Chandra, who had developed ‘burning mouth syndrome’ (a painful condition that ended her singing career) following damage to her vocal cords during a medical procedure in 2009.

Like TOTEMIC, Voces amissae concentrates on very delicately produced sounds, but, building on his experience with the earlier piece, Wilson enlisted the help of engineer David Stalling (of farpoint recordings) to shape the music’s sound in performance. This is an approach he believes he will take many times again: ‘There are possibilities sonically, dynamically. In a way, this is a summing up of things I’ve done in I Quattro Elementi and TOTEMIC, but the scale of it … It just feels like this big sphere at the end of a number of years’ work, and I feel like there is a number of arrows going in different directions.’

The last addition is the poetry of Serbian poet Draginja Adamović (1925–2000). Although Serbia has been an important part of his life for many years now, Wilson does not feel qualified to draw on it as a cultural resource. Adamović’s poems, which he discovered only in 2023, are the exception. Over my few days staying with Ian, her name came up almost more than anyone else’s: it is clear how moved and excited he has been by these texts. At one point, he shows me some translations he and Dušica have made into English. They are aphoristic and obscure, full of dark and surrealistic imagery: ‘The fish-eyed man / He followed my every step’; ‘The crucified sound trembles in the air’. The closest comparison that comes to mind is the work of the Hungarian Freudian-socialist Attila József, a favourite of György Kurtág, but if anything, Adamović’s lines are even more brutally terse. This quality makes them relatively easy to translate, says Wilson, but requires a different musical approach: he had to tap into something ‘almost prehistoric’ in his setting, a ritualistic, non-melismatic approach that pared away his usual lyrical impulse.

Today, Adamović is hardly read by anyone, even in Serbia. Thus, she qualifies as a different kind of ‘lost voice’. And the suppressed terror that he senses in her work makes it appropriate to the theme of physical or political silencing. With so many other voices heard through his piece, it was important for Wilson to use four of her poems in Voces amissae as structural ‘tent poles’ that could support the whole. Whereas the sections of the work that are based on interview material or published quotations retain the looser, conversational feel of their sources, the Adamović settings have a solidity and sense of permanence. (In offsetting the more ‘conversational’ passages, they perform a similar structural role to the Doris Day songs of Bewitched, although the aesthetic effect is entirely different.) The result is, for me, one of Wilson’s strongest works for some time. Voces amissae is a work haunted by pain, trauma and oppression, but balanced by strength and even optimism. In December 2024, Germany’s Ensemble Musikfabrik played it in their hall in Cologne – the first time this prestigious ensemble has performed Wilson’s music and a perfect way to round off a big birthday year.

And so our on-tape conversations are coming to an end. Wilson’s career has taken him to many different places, given him many different hats to wear. But even if some of those had more to do with expedience than artistic necessity, it is clear that at 60, he is as energised and driven as ever. His discoveries of the last few years – the amplification of quiet sounds, the construction of musical absences, the poetry of Draginja Adamović – have given him a focus he hasn’t felt in a long time. (And the ‘darker’ examples of his recent output that I have mentioned are complemented by an equal number of ‘brighter’ works, such as the chamber flute concerto When I Became the Sun, 2023, and the ‘everythingist’ Sonnatura, 2020, written for Mladenović and Tinney.) ‘I feel like there’s work to do now’, he concludes. ‘I have stuff to do.’

Back home, I tidy up the CDs, booklets, magazines and other papers that have become scattered across my study while writing this piece – paralleling my own journey alongside Wilson’s. Among them is the Riverrun disc of Sullen earth, featuring Hugh Tinney’s performance of Limena, that remarkable concerto for piano and muted strings from 1998 that so compelled me twenty-odd years ago. I can scarcely have listened to it since. It is often observed that musical time moves differently from clock time, and the time of musical memory is different again. To relisten to a piece is to remember all previous listenings, stacked on top of each other like photographic transparencies, but such that those layers of difference add up to greater, not lesser, clarity. You listen where you are now, but also in the knowledge of where you were then when you listened, and then, and then. And how the music moved you differently each time, each listening building on the sensation of the last.

So I put the CD on to listen once more. And those ringing piano Bs with which it opens send me back two decades ago, while the strings beneath melt the years of memory between into one glittering, glutinous flow. As the music proceeds, it twists slowly in on itself, its various elements presented at ever-decreasing intervals – ‘as though enclosing the piece in a hall of mirrors’, I wrote back then. Being wound together as though by a spinning wheel, I think now. A thread that can be picked up again, many years later, and woven into something entirely unexpected.

Tim Rutherford-Johnson, October 2024

Tim Rutherford-Johnson (left) in conversation with Ian Wilson (right)

Photo credit: Méabh Noonan