MU student Ronán Conroy writes on A.J. Potter's settings of Synge's translations of Petrarch

"I don't think I've ever done anything better": A.J. Potter's settings of Synge's translations of Petrarch

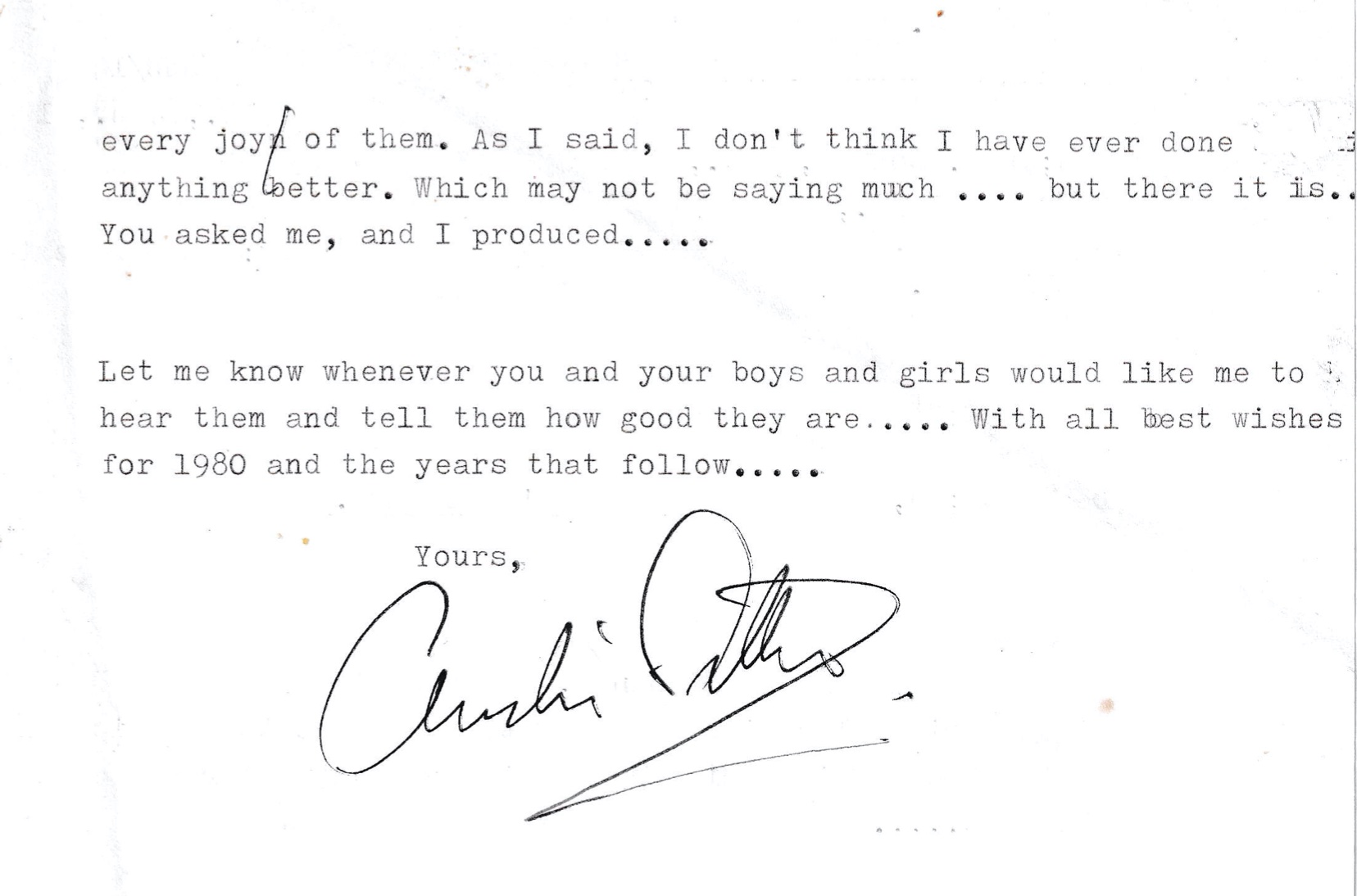

Extract from one of A.J. Potter's letter to Ronán Conroy.

Ronán Conroy is a musicology MA student in Maynooth University, part time. The rest of the time he is Professor of Health Research Methods in RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, in Dublin. His course placement with the CMC offered him an opportunity to revisit commissioning a choral work from A.J. Potter when documents and scores related to the commission turned up, having been lost for decades.

A.J. Potter (1918-1980) was born in Belfast to a poor family. It was his musical gifts, and an aptitude for hard work, that won him a choral scholarship to All Saints, Margaret Street in London, and later a scholarship to Clifton College in Bristol, eventually leading him to the Royal College of Music in London where he studied under Vaughan Williams.

Moving to Dublin in the 1950s, he devoted his life to teaching, lecturing and composition. A truly versatile composer and arranger, his output ranges from orchestral settings of traditional Irish music to major works such as

the Sinfonia de Profundis, a work written to exorcise the shadow of his traumatic experiences in the British army in World War II. Among his final works was a suite of four settings of Petrarch, in translations by JM Synge, which are the subject of this article.

I met A.J. Potter when I was a young research assistant working at the Mount Temple Music Research Unit, a curriculum development unit based in Mount Temple comprehensive school in Dublin, in the late 1970s. The director of the unit, Albert Bradshaw, commissioned him to write sight-singing exercises for our pupils based on Irish folk music – not necessarily exact tunes, but in the idiom. We were delighted as each batch arrived and we sang them through. They were utterly musical and completely singable.

So when, a year later, when I was offered funds by Peter L Moore to commission a work for the Saint Stephen's Singers, a chamber choir that I conducted, I thought at once of Potter. And by coincidence, I had just bought a copy of JM Synge's translations of Petrarch's sonnets on Laura in death. They seemed like the perfect texts.

Anyone who sings madrigals will have come across some of the hundreds of settings of Petrarch's poetry by renaissance composers. His poetry offers two great attractions for any composer. First and foremost, the poems are a peak of Italian literature. In particular, the sonnets written on the death of Laura, the woman he loved from afar, speak with a searing vividness of love and loss. And this was the second advantage: Petrarch's poems often contrasted the happiness of the past, or the beauty of nature, with his own wretched state – giving the composer a golden opportunity to depict these abrupt changes of tone in music.

Few people are aware that JM Synge, in the last years of his life, translated seventeen of Petrarch's sonnets in what George Watson called "one of the strangest and most haunting of all the oddities of the Irish literary renaissance". All of the translations were from in Morte di Madonna Laura, the poems that Petrarch wrote after the death of Laura.

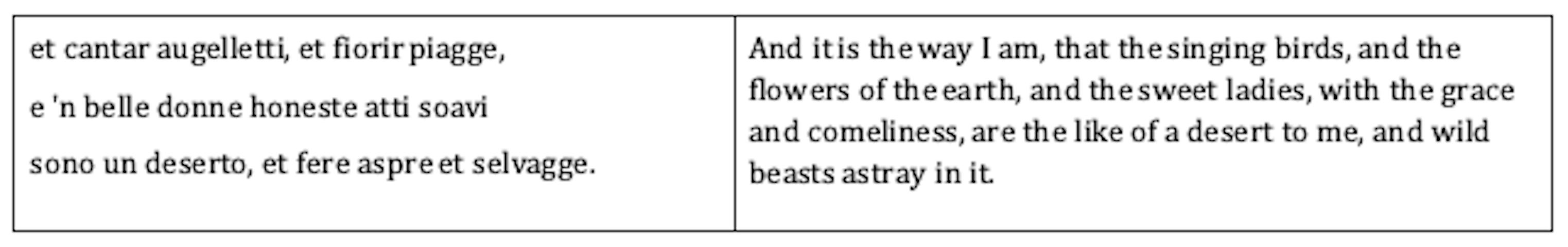

The most striking feature of these translations is that Synge does not try to make the poems sound in any way archaic. Instead, he translates them into the English idiom that he had fallen in love with in the Aran Islands. The very strangeness of the language he uses, the fact that we have to work a little at understanding, allows Synge to capture the vividness of the original. Here, for example, is a typical translation:

Petrarch's three lines of poetry have become a single unbroken declamation. And – true playwright that he is – he perfectly captures the bitter twist of the last line.

It seemed natural, then, to ask Potter to take the form of the madrigal as a starting point and to respond to it as a contemporary Irish composer, as Synge had responded to the original poems as a contemporary Irish dramatist.

The music also had to be performable by a (good) amateur choir! And it was here that Potter excelled – after all, he himself had been both a choral scholar and later a vicar choral. A consummate professional, no matter what instrument he wrote for, musicians recognised a composer who knew their instrument and how to get the best out of it. (I recall him, as a feis adjudicator, regaling the audience with a hilarious account of the difficulties of playing the trombone, punctuated, in true Archie style, with "but that is neither here nor there, but beside the point".)

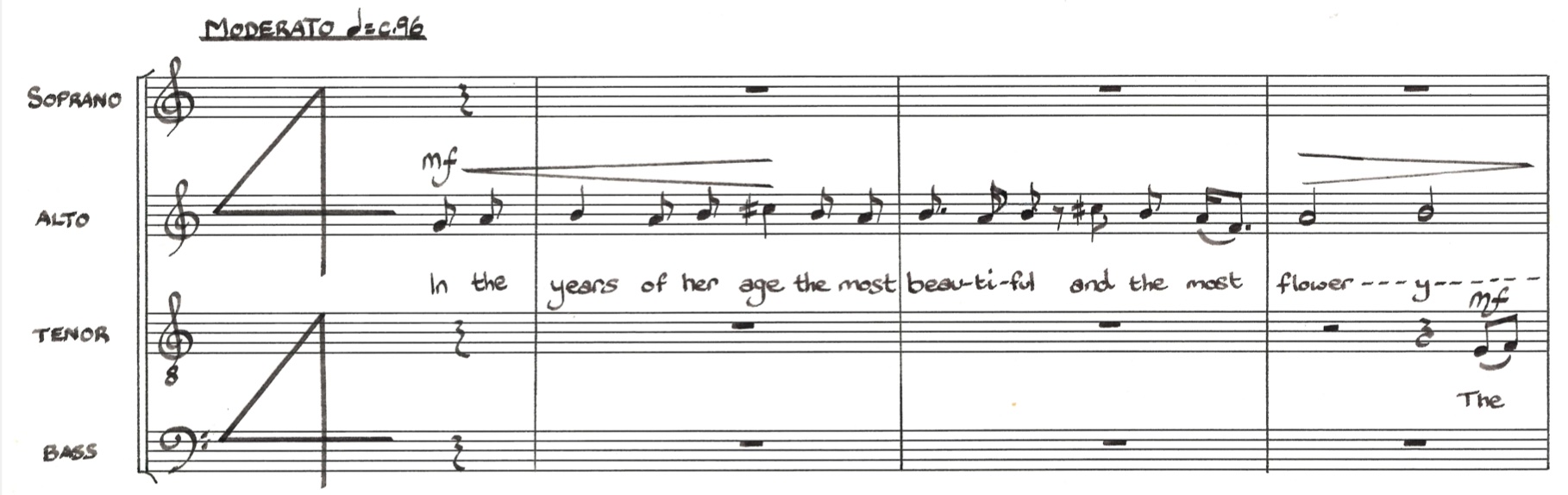

Potter took to the idea at once. I lent him the Synge translations, asking him to make a personal choice from the texts, and he set to work with a will, excitedly sending me the first setting with the ink barely dry. The choir sang it through. In the years of her age the most beautiful, and the most flowery sang the sopranos, alone. Answered by the tenors, alone. And the sopranos again: Laura, who was my life, has gone away, leaving the earth stripped and desolate. The unaccompanied vocal lines, the silence of the other voices, gave the opening a haunted, desolate quality. Only slowly did the full choir enter, the music building through a series of climaxes to its final bars: Oh, what a sweet death I might have died this day, three years today. Like any madrigal, the music followed the ebb and flow of the text perfectly, responding to the light and shadow without ever losing a sense of ultimate direction.

The opening of the first piece, in Sarah Burn's fair copy

The rest of the settings followed swiftly. He set four of the poems, their order paralleling the movements of a symphony, giving them a strong sense of coherence and direction.

And then, to my delight, I got a call from him. He was putting together a portfolio to submit to the Arts Council. Would we mind recording the pieces? Of course – we jumped at the chance. And in a room at the top of Newman house, on a beautiful spring evening in 1980, we gathered to record them. Stephens Singers were understandably a little nervous at having the composer present. We need not have worried. His warmth and enthusiasm set us all at our ease. From being fearful of getting things wrong, suddenly everyone just wanted to sing for pleasure. If we were hoping for tips and corrections from Archie, we were mistaken. He just beamed with complete and unfeigned delight.

I can't resist quoting Archie's letter that came when he returned the tape. By this time, his letters about the project had long ceased to be brisk and business-like and greatly resembled his conversational style.

As I said, I don't think I have ever done anything better. Which may not be saying much... but there it is... You asked me, and I produced...

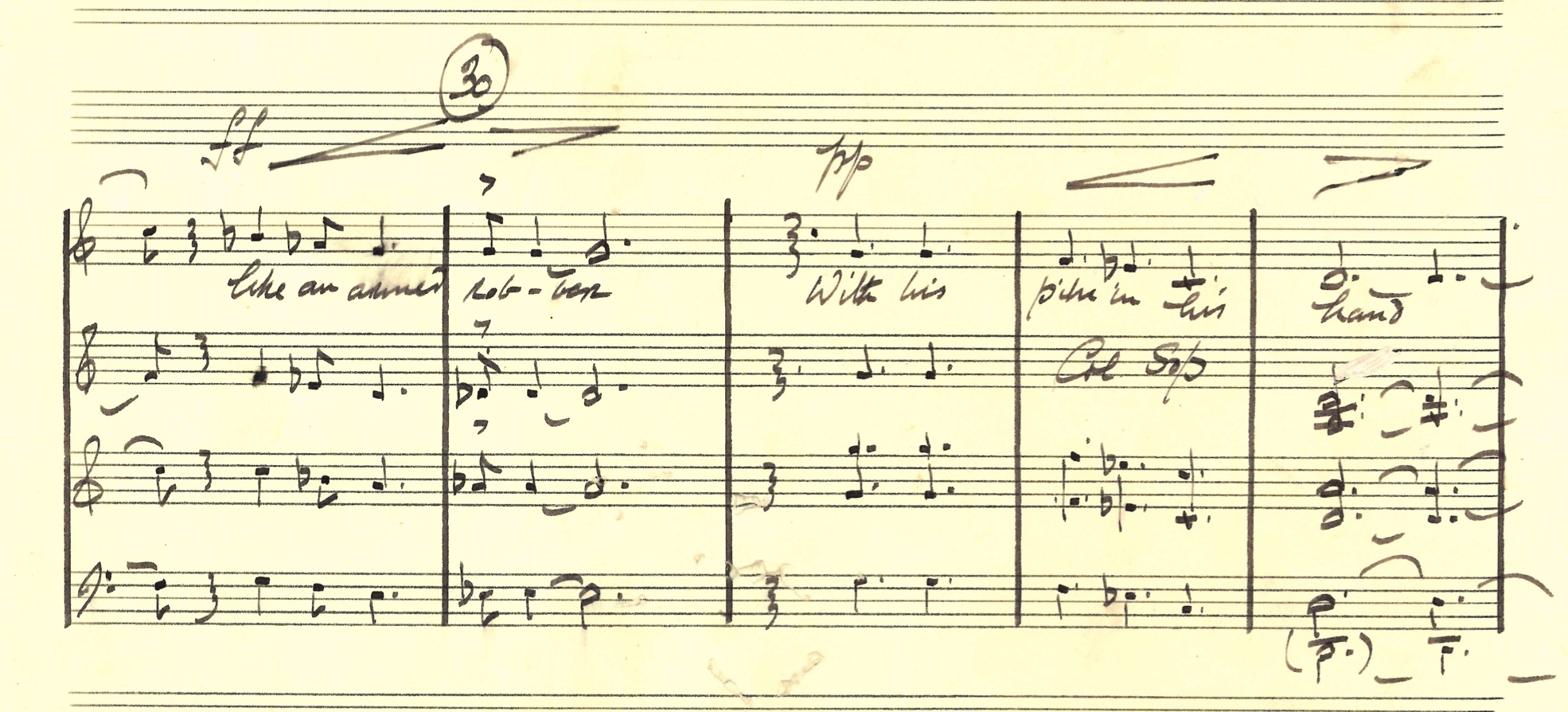

The settings are indeed among his best works, all the more remarkable for the concision and economy of the writing. They are alive to the tensions in the text between loss and loneliness, on one hand, and eroticism and yearning on the other, perfectly captured in his setting of the description of Laura, in heaven, as "living and beautiful and naked". And the abrupt onset of darkness that characterises the poems produced harrowing passages, such as this one, where Potter sets the text But Death had his grudge against me, and he got up in the way like an armed robber with a pike in his hand.

'Like an armed robber with a pike in his hand' from Potter's autograph score

The vehemence of the text is echoed in the grating harmonies and sudden dynamic contrast, and Potter's own vehemence is clear from his handwriting!

These scores, together with Potter's letters, which for years I believed lost, fortuitously turned up again recently. The pieces have been newly typeset by Sarah Burn, and I am happy to know that they will be available for performance, and that a late masterpiece by one of Ireland's most significant composers can be heard in all their beauty and strangeness.