Through the Digital Door: Stanford September Special 2024

This year marks the centenary of the death of Irish composer, Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 - 1924). In this edition of Through the Digital Door, guest author and Stanford specialist, Dr Adèle Commins, shares her research on the comic opera Shamus O'Brien.

Discover the origins and context of the opera, which has been recently recorded and released by Retrospect Opera, ahead of the Stanford Festival next month (October 11th-13th).

The audio extracts in this feature are taken from Shamus O'Brien (RO011), and are reproduced by kind permission of Retrospect Opera.

Despite Charles Villiers Stanford’s departure from Ireland in 1870, the music of Ireland was an important source of inspiration for his creative outputs.* The comic opera Shamus O’Brien op.61 from 1895, his only opera set in Ireland, is a notable example. Subtitled ‘A Story of Ireland 100 Years Ago’, the story is based on a poem by Dublin-born Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814–1873) with a libretto written by Longford-born playwright George H. Jessop (1852–1915). Completed in 1895, it is set in the fictional village of Ballyhamis, Co. Cork in the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion. It is the most successful of Stanford’s operas as it caught the imagination of audiences in England, Ireland, America, Germany and Australia.

Story of the Opera

Shamus O’Brien was written and staged in the period nearing the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion. Shamus O’Brien, the rebel, was wanted by the British Army and he continuously outwits the British soldiers. The villain of the story, Mike Murphy, was jealous of Shamus for marrying Nora and he betrayed Shamus to Captain Trevor. Although at first he evaded capture by disguising himself as the village idiot, with the help of Father O’Flynn, the Catholic priest, Shamus was later apprehended and condemned to death. As Father O’Flynn was giving Shamus his final blessing, he escaped and ran to the hills. The love triangle between Shamus, Mike and Nora adds another facet to the opera and is contrasted with the love interest between Nora’s sister Kitty and Captain Trevor.

Audio-only recording of Shamus O'Brien made by Radio Éireann, 1968.

Performances of Shamus O’Brien in Ireland

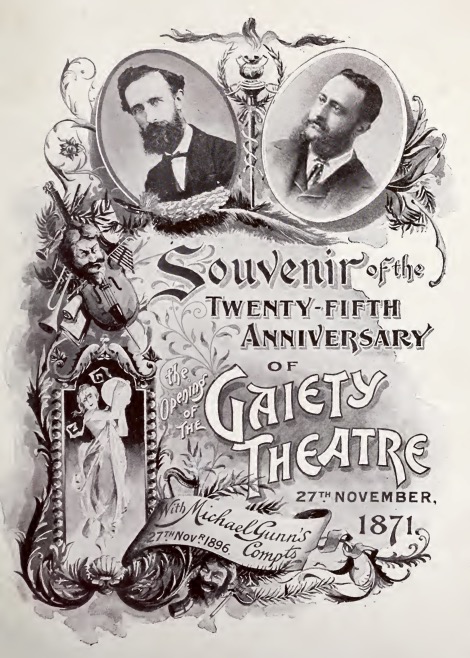

Following a run of eighty-two performances at the Opera Comique in London beginning on 2 March 1896 followed by a tour of the English provinces, the production was staged in Ireland, concluding in Dublin as part of the 25th anniversary celebrations of the Gaiety Theatre, with two performances conducted by Stanford. The inclusion of the opera in the celebrations was particularly noteworthy given that so few of Stanford’s large-scale works had been performed in Ireland up to this point.

Cast of the Opera

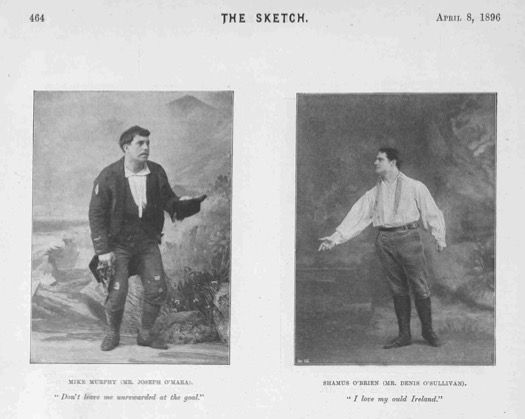

A significant aspect of productions of Shamus O’Brien was the number of Irish performers involved. Performers included the renowned Limerick-born tenor Joseph O’Mara in the role of Mike Murphy. He was replaced by Edwin Rennie from Newry, Co. Down for most of the second tour of Ireland as O’Mara was engaged for performances in America. Lucy Carr Shaw, sister of George Bernard Shaw, undertook the role of Kitty O’Toole for the first tour of Ireland and the tour of America, while Birdie Conway from Cork played the role of Kitty during the 1897 tour of Ireland. American-born singer, Denis O’Sullivan, whose father was from Skibbereen, Co. Cork, performed the role of Shamus O’Brien at the premiere performance in London and returned for the American tour. Cork-born Charles Magrath participated in the English and Irish performances and returned for the Dublin performance in 1924. The following image shows O'Mara and O'Sullivan in their respective roles.

Depicting and Representing Ireland

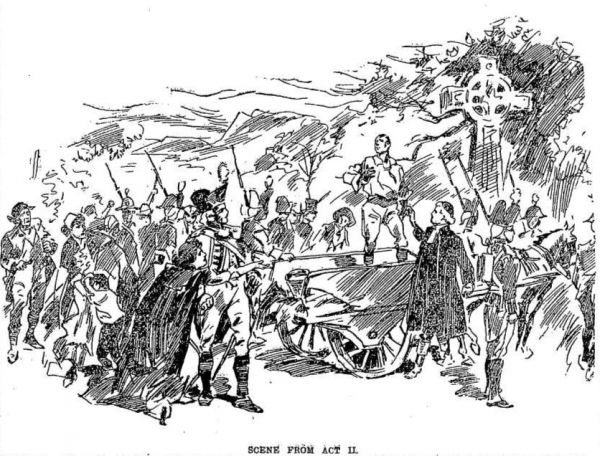

In his depiction of Ireland Stanford set out to create an authentic setting and soundworld. The opera musically references Stanford’s homeland through its use of melodies suggestive of Irish airs and inclusion of jigs, reels, the 'caoine' lament, and a character who performs on the uilleann pipes. Other references touch on aspects of Irish folklore, such as leprechauns and fairies. Most obvious of the Irish references is Stanford’s use of the popular jig, Father O’Flynn, which was included in Songs of Old Ireland, a collaboration between Alfred Perceval Graves (1846–1931) and Stanford in 1883. The set reflected imagery of Ireland including the romanticised countryside with the traditional stone cottage, High Cross and the village dance scene.

Image credit: Evening Herald, November 21st, 1896.

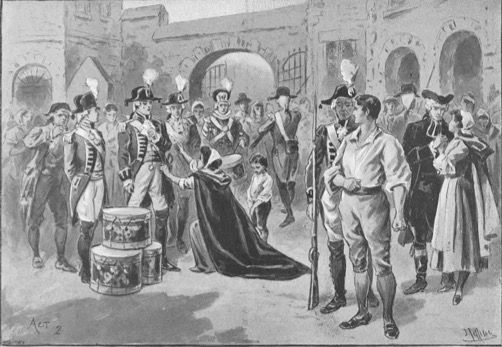

Other images clearly portray many of the emotions during the production. In the Barrack Square scene Nora pleads with a British soldier for the release of her husband Shamus, who is restrained by another soldier.

Image credit: The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, March 21st, 1896, p.88.

Stanford included an old piper for the village dance scene. A writer in The Times commented positively about the Irish bagpipe: ‘an instrument of which the sweet, soft tones are in strange contrast to the screechings of the Scottish variety.’ (Evening Mail, March 4th, 1896, p.3)

Reception

The popularity of Shamus O’Brien in Ireland is outstanding in comparison to other works by Stanford. Irish people could respond to the story and to the music; there was a sense of parochialness to the work. The lightheartedness of the storyline with the portrayal of the different characters including the heroine and the villain coupled with the love themes made it accessible to a wider audience.

Image credit: The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, April 11th, 1896, p. 208.

Critics focused on the humorous aspects of the plot and commented positively on the Celtic flavour, Stanford’s masterly orchestration, the vocal scoring, his versatility, his handling of Irish melodies and his command of melody. The opera was a production of international standing. Shamus O’Brien lost its place in the repertory following Stanford’s decision to withdraw the opera from public performance in 1910 until after his death. The opera was revived at the Aonach Taillteann in Dublin on 11 August 1924 under the direction of Joseph O’Mara.

Image credit: The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, April 11th, 1896, p. 208.

Shamus O’Brien Today

In March 2024, Retrospect Opera released a new recording of Shamus O’Brien with the Orchestra of Scottish Opera conducted by David Parry, along with Opera Bohemia Voices and a range of soloists with the Irish characters sung by Irish singers. Using a new edition prepared by Valerie Langfield, the release of this CD was a significant undertaking and an exciting project to be completed during the centenary year. It is hoped that this new recording will encourage greater interest in the opera, and in Stanford’s music in Ireland.

Extract: Finale from 'Shamus O'Brien', Retrospect Opera.

More on Retrospect Opera and the new recording can be found here.