Ronan Guilfoyle on Thelonious Monk

2017 is the centenary year of Thelonious Monk, and composer, jazz musician and educator Ronan Guilfoyle is currently writing a piece celebrating this iconic figure. He writes about the new piece and the influence of Monk on his music.

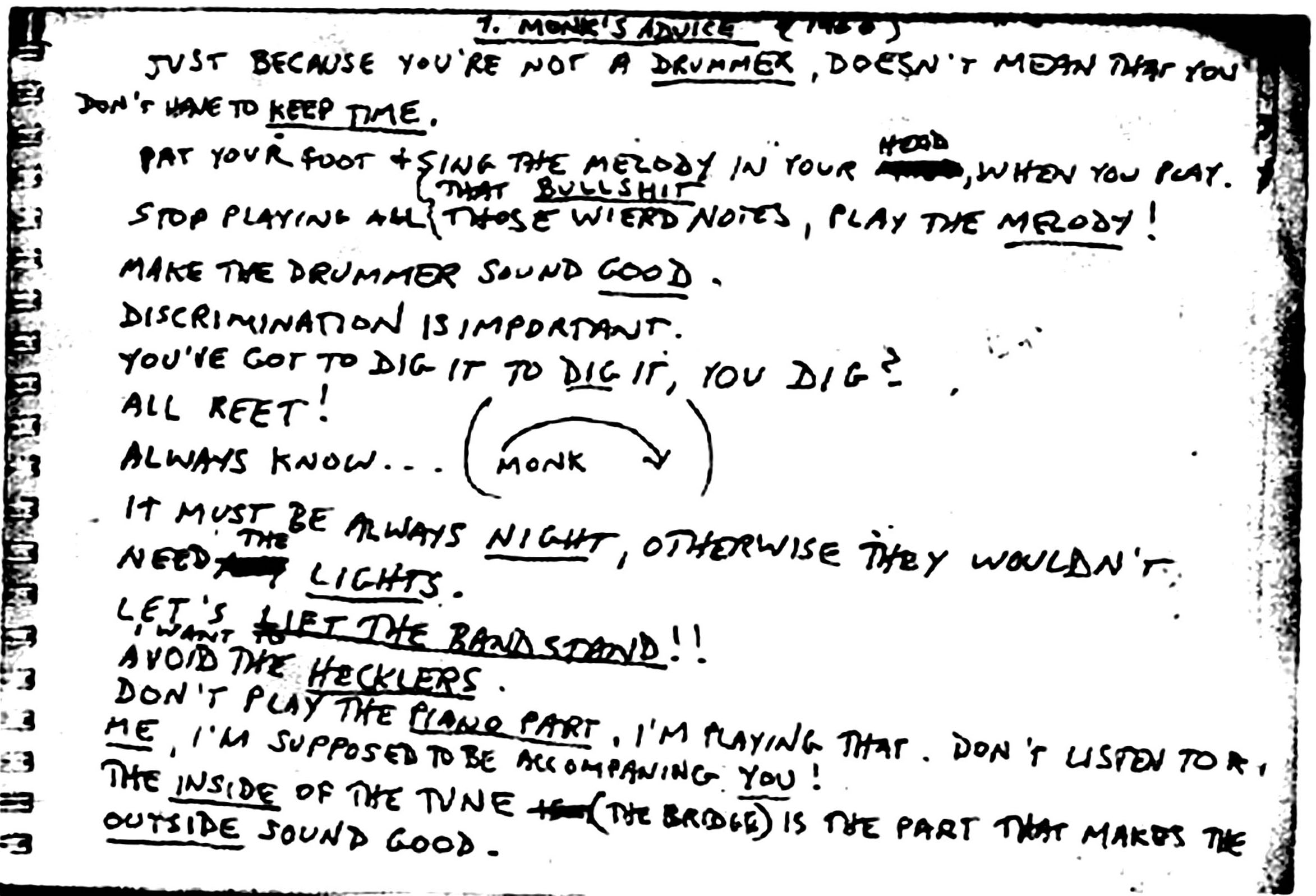

Just before going on stage, Thelonious Monk would often deliver this particular piece of advice to his band: ‘Don’t forget, always know …’ A typically gnomic piece of advice from one of the masters of the gnomic utterance. What it was that was to be known was never specified, but of course was always enough to get the mind working on the part of the band members. Monk was famous for these nuggets of wisdom in which nothing was said, yet everything was said. He was not a man given to lengthy verbal explanations, but left it up to the people he was speaking to to interpret and understand what he was saying in whatever way they chose. In the early 1960s the saxophonist Steve Lacy, who was then a member of Monk’s band, started to jot down these throw-away sayings, and the piece of handwritten A4 paper on which he wrote this information has appeared online in recent years under the heading ‘Monk’s Advice’.

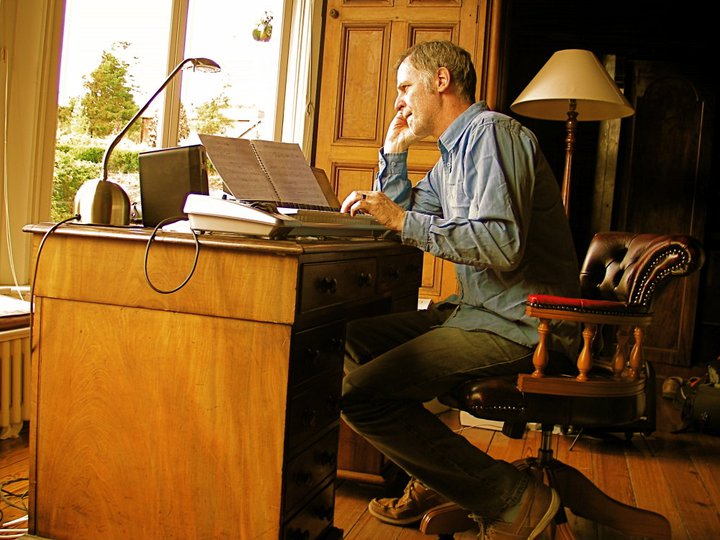

This year is the centenary of Thelonious Monk’s birth, and I recently spent some time at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre writing a piece for septet that will celebrate one of the great composers and jazz musicians of the 20th Century. When I was about 12 years old my father brought home a double LP featuring a selection of Monk’s music. Although familiar with jazz through my father’s record collection, I had never heard anything like this. The angular melodies, the sparseness of the backgrounds, the slightly off-kilter, but very deep swinging beat immediately caught my ear, and I listened incessantly to those LPs. It’s not surprising that I hadn’t heard anything like this, because there really was nothing like Monk, either in jazz or outside it. Brilliant Corners, the first track on my father’s LP, is unlike anything else in jazz, or anything else in 20th century composition either. Its strange angles and wide intervallic leaps, connected to a swinging beat, created a sound-world all of its own. Or all of Monk’s own. Since then I have listened to pretty much everything he ever recorded, and seen all the YouTube videos of live performances, watched the documentaries, and read the biographies. I have formed bands dedicated to playing his compositions, I have immersed myself in Monk’s musical, and latterly - through Robin Kelley’s exhaustive biography - personal world.

He is one of those figures who becomes even greater the more you study him and the more you learn about his music and his attitude to life. He was an eccentric man, and these days would probably would have been diagnosed as Bi-polar. But his music is utterly original, both compositionally and pianistically, and is all of a piece with his personality – quirky, humorous, swinging, dance-able (he loved to dance to it himself, as you can see on the live videos), and with an underlying poignant lyricism, especially on the slower pieces. He also was the possessor of a completely original piano sound - often derided at the time for its lack of alignment to what constituted a ‘proper’ piano technique, but now recognised as one of the most unique sounds in jazz.

Ronan Guilfoyle at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre

When considering how to approach the writing of this piece, (it will be a suite in approximately seven parts), I wanted to avoid the kind of shallow clichés so often delivered by jazz composers when trying to write in a ‘Monk style’. The gestures used by many to represent Monk’s music, (using upper register cluster chords in a triplet rhythm is a particularly common abomination), are by now so predictable as to be beyond parody, and I wanted to steer resolutely clear of this lazy approach. When I think of the essence of Monk’s music, i.e. those elements without which Monk’s music wouldn’t be identifiable, the two indispensable facets would be groove and some elements of the blues. Yes there are other common characteristics, including the preponderance of wide intervals and unpredictable rhythmic accents, but blues and groove are always there. So I decided that no matter what I would write, the music needed to be informed by one or both of these elements.

Then I thought about what material I would base the pieces on, and decided that I didn’t want to write pieces that were essentially paraphrases of Monk’s own music. That would be a sure-fire way to set yourself up for the kind of comparison in which there would be only one winner. I decided that a far more interesting and ultimately more apposite approach would be to base the pieces on the various sayings contained in the aforementioned ‘Monk’s Advice’ document. This has proved to be a very fertile area for inspiration, and I’ve been combining what I believe to be the indispensable musical qualities that always feature in Monk’s pieces, with ideas gleaned from the aphorisms of Monk as expressed to Steve Lacy. How could you not be inspired by such mysterious gems as:

‘It’s important to discriminate’

‘Make the drummer sound good’

‘Stop playing all that bullshit and play the melody!’

‘When you’re swinging, swing some more’

‘Always know…..’

‘The inside of the tune is the part that makes the outside sound good’

‘Don’t play everything, let some things go by’

These sayings and other remarks contributed at the time to Monk’s reputation for eccentricity, but with the benefit of hindsight and the wealth of personal detail uncovered by recent Monk scholarship, it’s clear that these sayings constituted a consistent personal and musical philosophy that underpinned all of Monk’s work. It is the meaning contained in these words - the commitment to swing and groove, to paring music back to the essentials, to making every note mean something, that has been the inspiration for me in writing this suite. Rather than thinking explicitly of the music of his that I know so well, I’ve been thinking of the thought processes he used when composing this music and using that as the springboard for my own music.

Monk’s stature in the jazz world and world of art has grown year on year – his image in the public consciousness has evolved from being regarded as an eccentric aberration of the bebop period, to being considered as one of the most important jazz composers and performers of all time, and he is now regarded, (as shown by the making of the Straight No Chaser documentary by Clint Eastwood) as an American cultural icon. He was a true original, both in music and in life - you just have to listen to a few bars of his music to hear it. As he said himself:

You’ve got to dig it, to dig it - you dig?