MU students Monika Martinovic, Rose Cameron, and Samuel Shortall write about Seóirse Bodley work

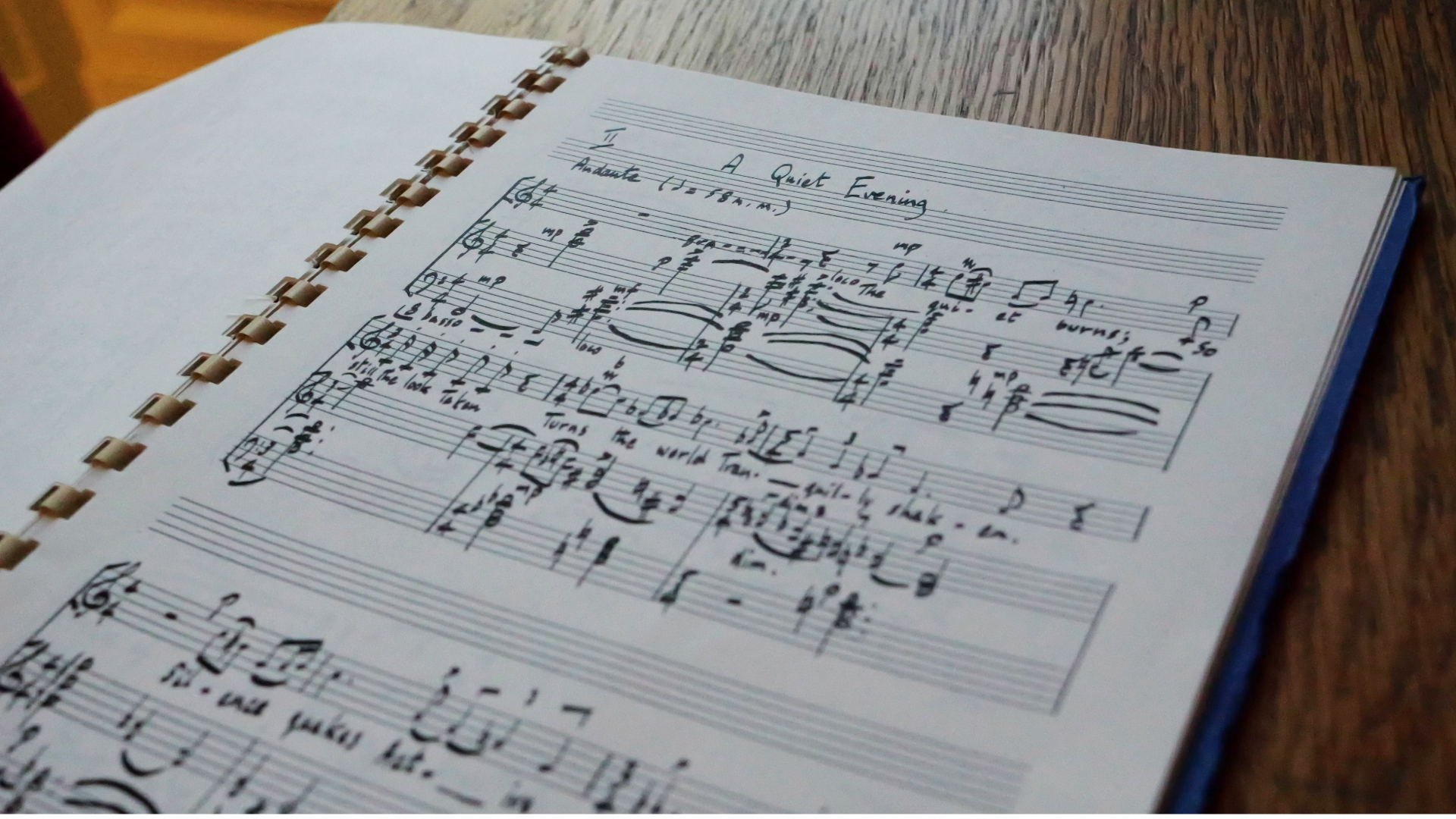

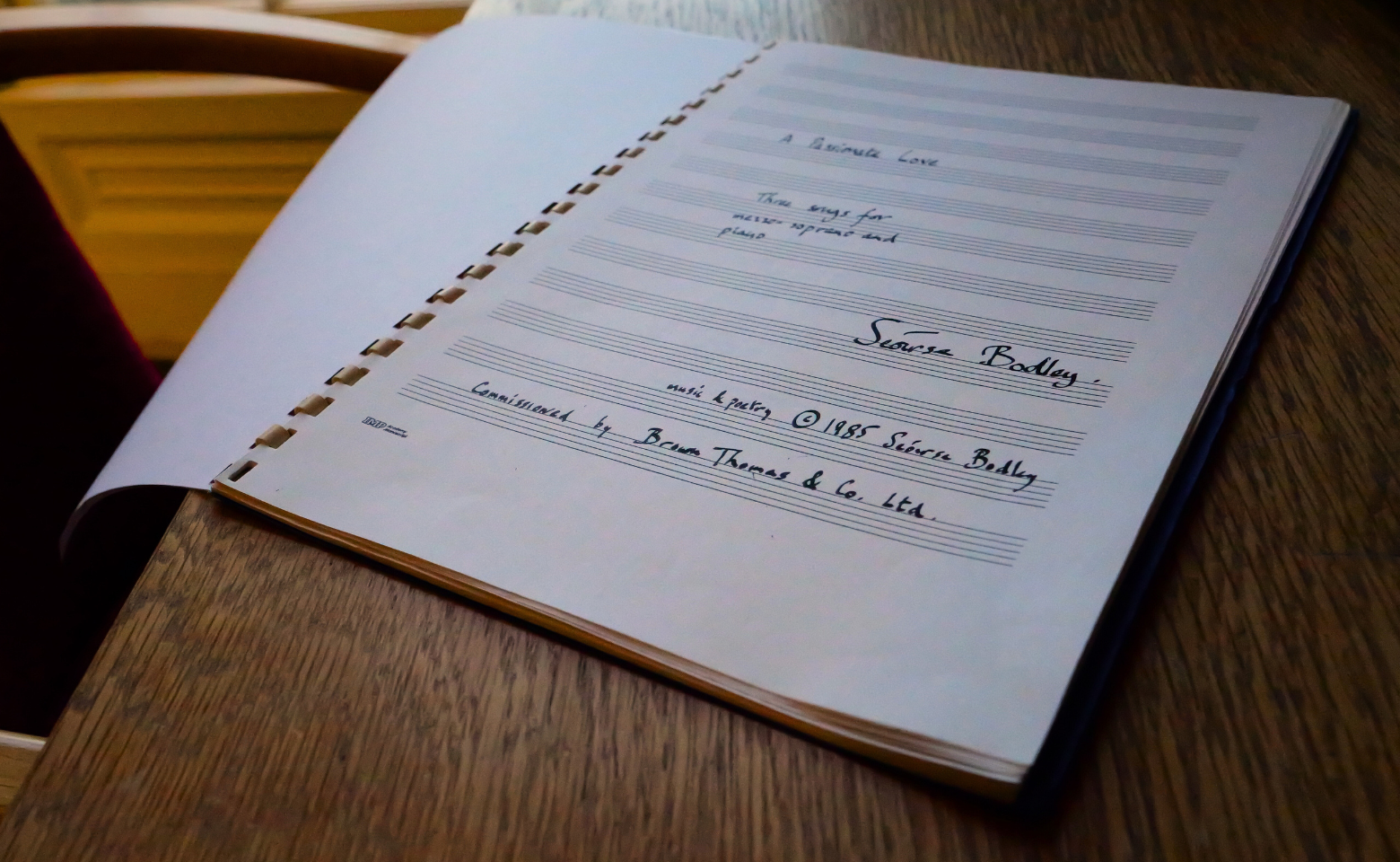

In Spring of 2024, three students on the MA in Performance and Musicology at Maynooth University completed a placement at the CMC Library as part of their "Research Methods" module. Working with a copy of the original handwritten score of Seóirse Bodley's 1985 song cycle A Passionate Love held in the CMC Library, and a live recording of the work held in the CMC Audiovisual Archive, students Monika Martinovic, Rose Cameron, and Samuel Shortall prepared a typeset edition of the score, and a short essay dealing with issues of historical context and musical style germane to the work. This work was completed with support from the CMC Library & Archive team. The typeset score is now held in the CMC Library as a digital file, and the students' essay is reproduced below. (Audio examples are by the students.)

(photo credit: Aileen Cahill)

On Seóirse Bodley's A Passionate Love

by Maynooth University MA in Performance and Musicology students Monika Martinovic, Rose Cameron, and Samuel Shortall

I. Historical Context and Background Information on Seóirse Bodley (by Monika Martinovic)

Europe was in a state of desolation and interested in trying to find new ways to move forward in the arts in the wake of the destruction of World War II. In the art music scene, this meant on one hand, the complete rejection of old thinking patterns, and on the other hand, attempts to find an appropriate musical response to, and reflection on, the horrors of the past. The idea of a Stunde Null and the wish for radical new beginnings marked the emergence of new musical styles and genres. The term Stunde Null (zero hour) was used in Germany and Austria to signify the end of the war and the opportunity for a restart. One of the most prevalent happenings in this context was the invention of serial technique. One particular strand of serial composition known as "total serialism" attempted to control all musical parameters according to strict rules. The rejection of any form of hierarchies had philosophical and political resonance.

At the same time, the musical developments in Ireland differed from those of Central Europe. Modernist ideas didn’t get a foothold until the 1960s and even then never bloomed in the way they did in the musical centre of modernity. Reasons for this phenomenon could be the peripheral position of Ireland to Central Europe and the lack of investment in music under colonial governance (Fitzgerald 2018:347). If we view music as a response to historical events, it would also make sense for Ireland to have a differing approach regarding musical developments: As countries like Germany and Italy were grappling with the human abysses caused by Nazi ideologies, Ireland, having played a neutral role in the war, was still in the beginning stages of newfound independence from Britain. The strengthening of a national identity was most important, therefore the nurturing of Irish traditional music would naturally become the central concern. Simultaneously, some considered art music associated with elitism and incompatible with Irish traditional music (Fitzgerald 2018:347).

One of the main figures attempting to break through this dichotomy was the Irish composer Seóirse Bodley. By using musical elements of both art music and folk music, he put two differing styles side by side and attempted a synthesis. In doing so, differences as well as compatibilities became apparent. Taken in a historical context, this also represented a meeting of two differing cultural histories: a search, perhaps, for Ireland to find its place in Europe. In other words, Seóirse Bodley's works were the compositional manifestation of the musical and political discourse taking place in Ireland and Central Europe at the time. The development of this discourse can be seen in the different approaches to incorporating these musical elements in his compositions throughout his career: In the beginning stages of Bodley’s career, his focus was on arranging Irish folk songs and setting Irish poems to music. He experimented with dissonant elements but wasn’t so much influenced yet by modernist ideas (1950s). This changed when he visited the Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music in Germany (1963, -64, -65). Influenced by composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, and Pierre Boulez, the avantgarde style came to the forefront of his compositions. Serialism and aleatoricity started to dominate his works. A shift in this approach happened when elements from Irish traditional music became central to his works and avantgarde styles were only used to inflect the meaning of text passages and as special effects (1970s). He slowly even abandoned avantgarde styles and turned to a neo-romantic tonal language. Bodley did find his way back to his avantgarde roots. His later works show a merging of both styles in a new way (1980s – 1990s). This compositional period is where A Passionate Love, a three-piece song cycle written by Seóirse Bodley in 1985, is set. The songs are dominated by a neo-romantic style with avantgarde and Irish traditional elements mostly used as ornamentations.

(photo credit: Frances Marshall)

II - Some Remarks on the Vocal Line in Seóirse Bodley’s A Passionate Love (by Rose Cameron)

A Passionate Love is of particular significance in Bodley’s vocal compositions from a text setting perspective, as the music is set to Bodley’s own poetry. In an RTÉ programme of Bodley’s music, he discussed both the advantages and difficulties faced by a composer whenever they write their own text for compositions, and how the composer will "know what is musically effective as well as verbally right" (Bodley, RTÉ Interview, 1986). This comment of Bodley’s is strongly reflected in the thorough text setting throughout this song cycle that is truly sympathetic to the natural speech rhythm.

A Passionate Love is not an anomaly in Bodley’s compositions as it is the second work of his that is set to his own texts, following The Banshee in 1983 and preceding The Fiddler in 1987 – which suggests Bodley’s interest in this text setting approach (Klein: Grove Music Online, 2001). However, within Bodley’s vocal output, much of his music was set to texts by Irish poets such as Micheal O’Siadhail and W. B. Yeats. This not only emphasises the poignance of A Passionate Love but also compliments and provides a further link to the strong Irish influence found in his pieces.

It is rather interesting to observe the reception of the song cycle with respect to the role of Irish traditional music, as, although Bodley was heavily influenced by traditional music, in a review in The Irish Times of the premiere of A Passionate Love (Boydell, 1986), Barra Boydell noted that

The influence of Irish music, formerly such a feature of Bodley’s music, largely recedes here in favour of a vigorous, passionate, and fundamentally tonal idiom of considerable power and intensity.

Although this review implies that Bodley’s traditional influences are not as prominent in this piece, the stylistic elements of traditional music are suggested by Bodley himself as on the first page of the score, there is a table of ornaments suggesting how they are expected to be sung. Furthermore, Bodley also writes that "The ornaments are taken from Irish traditional music" (Bodley: A Passionate Love, 1985). This ornamentation is a key feature throughout the song cycle but is particularly effective in the third movement, "A Human Voice". Within the first three lines, there are four mordents which epitomise the flowing and free line that is commonly found in traditional music, and present the strong essence of the Irish influences in the song cycle. However, the vocal line in the first song "Aflame", contrastingly, is more declamatory in nature, and shaped by expressive chromaticism and extensive dynamic markings, as well as the minimal use of ornamentation compared to that of the other two songs in the cycle.

"A Quiet Evening" is the second song in the cycle and offers a more reflective and pensive atmosphere throughout. The various styles and influences in Bodley’s vocal line are prominent in this song and "A Quiet Evening" epitomises Axel Klein’s description of how Bodley "…sought to develop a musical language that is recognizably Irish but maintains a cosmopolitan perspective" (Klein: Grove Music Online, 2001). One of the most striking features in "A Quiet Evening" is Bodley’s care and consideration for the text, which is reflected in his use of various markings, including staccato and marcato, and triplets, to mirror the natural speech rhythm and emphasise significant words or phrases. For example, the use of rests and staccato markings on the line "In the stillness, Silence thunders" (Figure 1) successfully mirrors the nature of the line.

Figure 1 – Bodley, "A Quiet Evening", bars 18-23

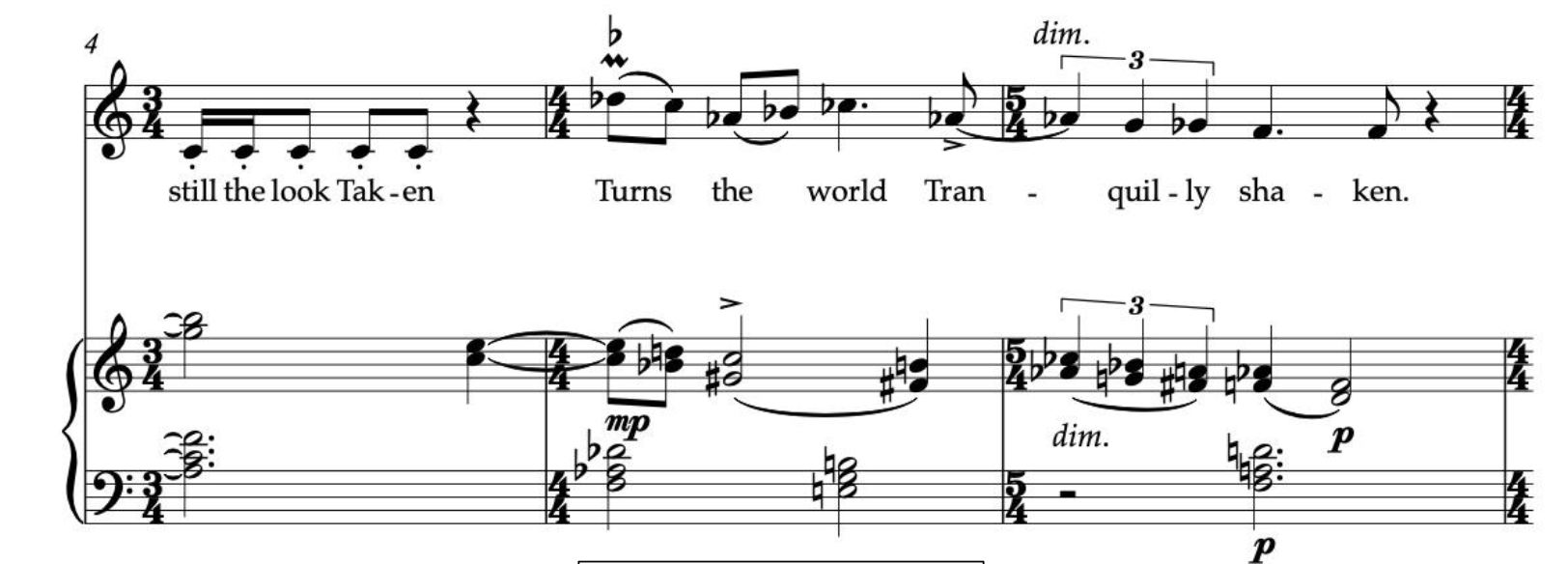

Contrastingly, the opening lines are more legato, and the natural speech rhythm is prominently reflected in the slurred quavers and the triplets in "Turns the world Tranquilly shaken" (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Bodley, "A Quiet Evening", bars 4-6

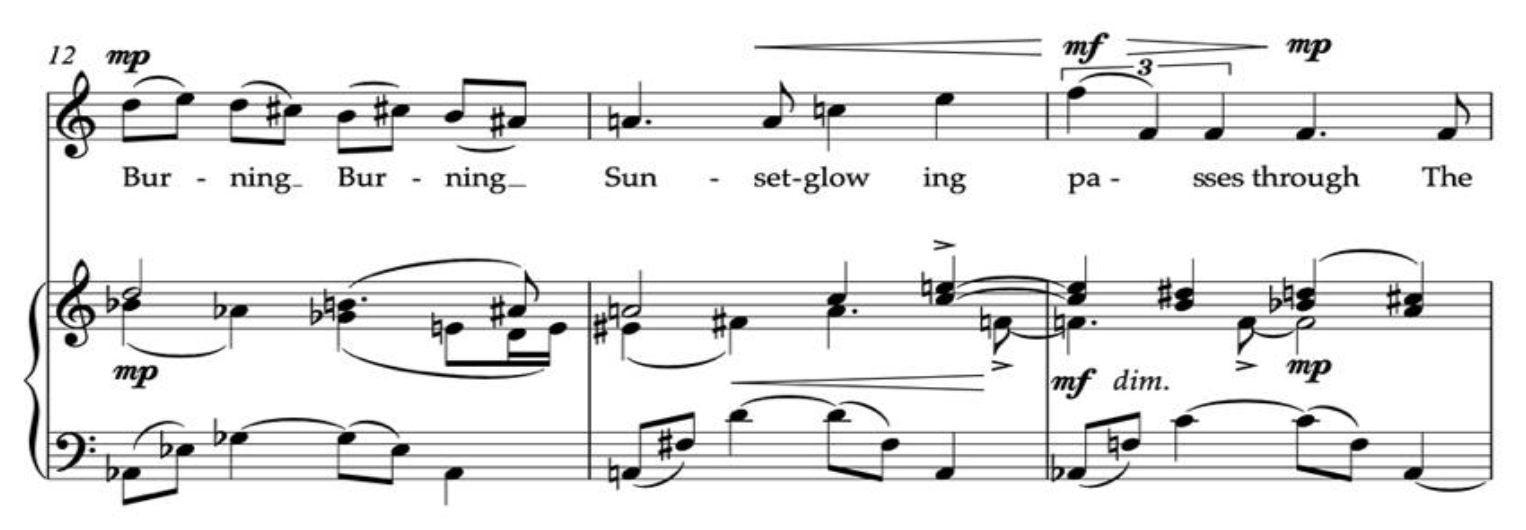

As mentioned, a key trait in Bodley’s music is the fusion of various styles which is particularly evident in the line "Burning, Burning" (Figure 3). The line is carefully and effectively written to emphasise the idea of tonal ambiguity that is prominent throughout the song cycle whilst also maintaining a sense of lyricism.

Figure 3 – Bodley, "A Quiet Evening", bars 12-14

(photo credit: Aileen Cahill)

III. Pianistic Style in ‘A Passionate Love’

The influence of Irish traditional music in Bodley’s vocal compositions can be seen not only in his vocal writing, but also in the writing for piano accompaniment. His use of ornamentation in the vocal line is present to an equal extent in the piano part and, in addition to this, the sparseness of Bodley’s piano accompaniments evoke a sense of freedom and rubato, as is typical in the Irish Sean-Nós tradition. Yet, by the same token, there can be little uncertainty about the influence of modernist musical characteristics on his writing, which is particularly evident in the piano writing.

The first song in the cycle deals with, as Bodley himself put it (Bodley, 1986),

"[…] the ambivalent nature of passion, the mixture of positive and negative feelings, the assertion thrown in the face of fate."

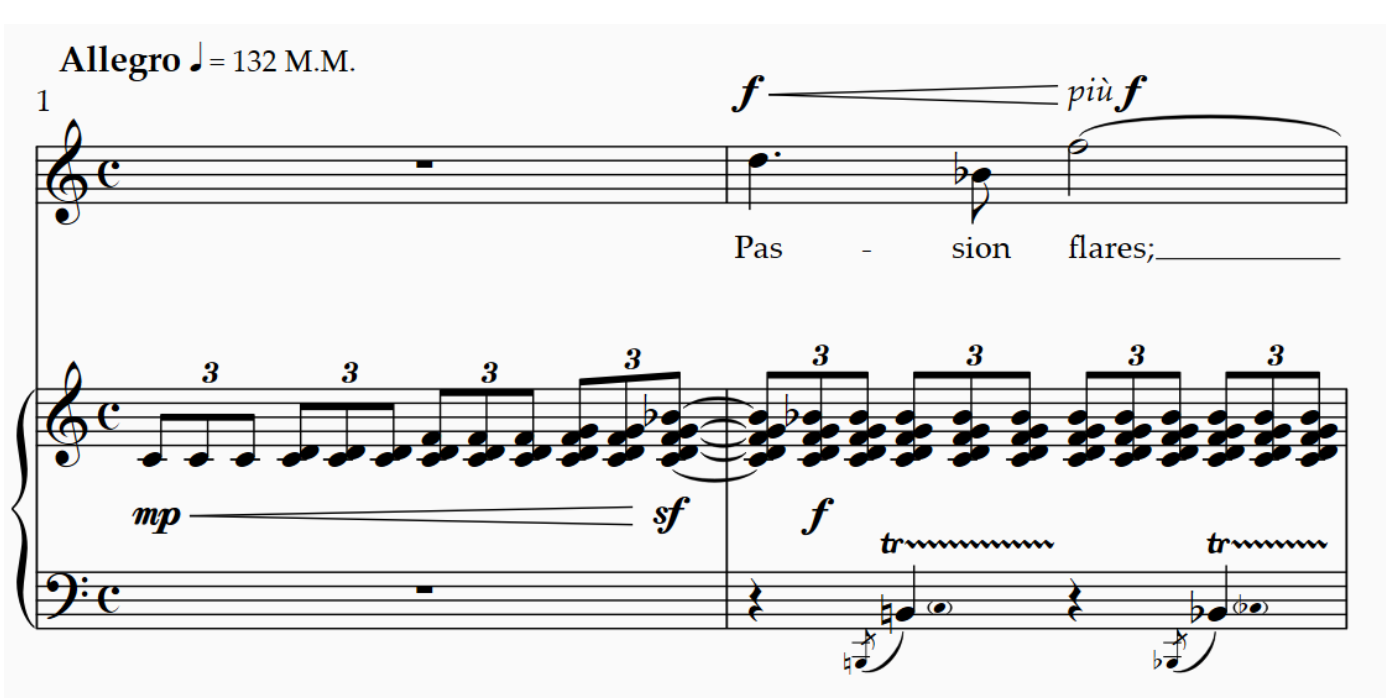

The atmosphere of the first two stanzas of Bodley’s poem is fiery and, as he mentions, evokes passion, which is cleverly portrayed by the agitated, brisk triplet chords in the right-hand piano accompaniment.

Figure 4 – Bodley, "Aflame", bars 1-2

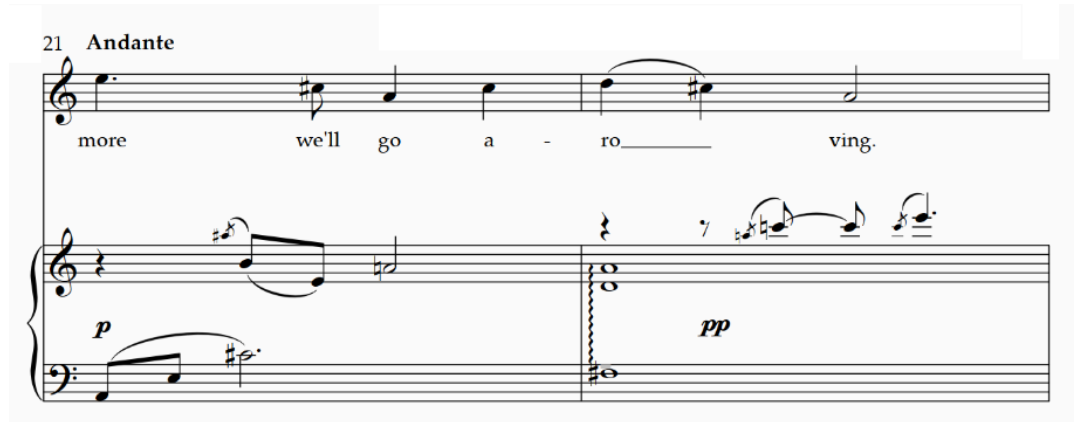

This accompaniment style is the most frequently used throughout the song. At stanza 3, however, it is staccato and dance-like, but before long, it and the vocal part become lyrical and subdued on the line "No more we’ll go a-roving". The atmosphere here has the feeling of settling in an A major sonority; until this point, the song remained tonally ambiguous.

Figure 5 – Bodley, "Aflame", bars 21-22

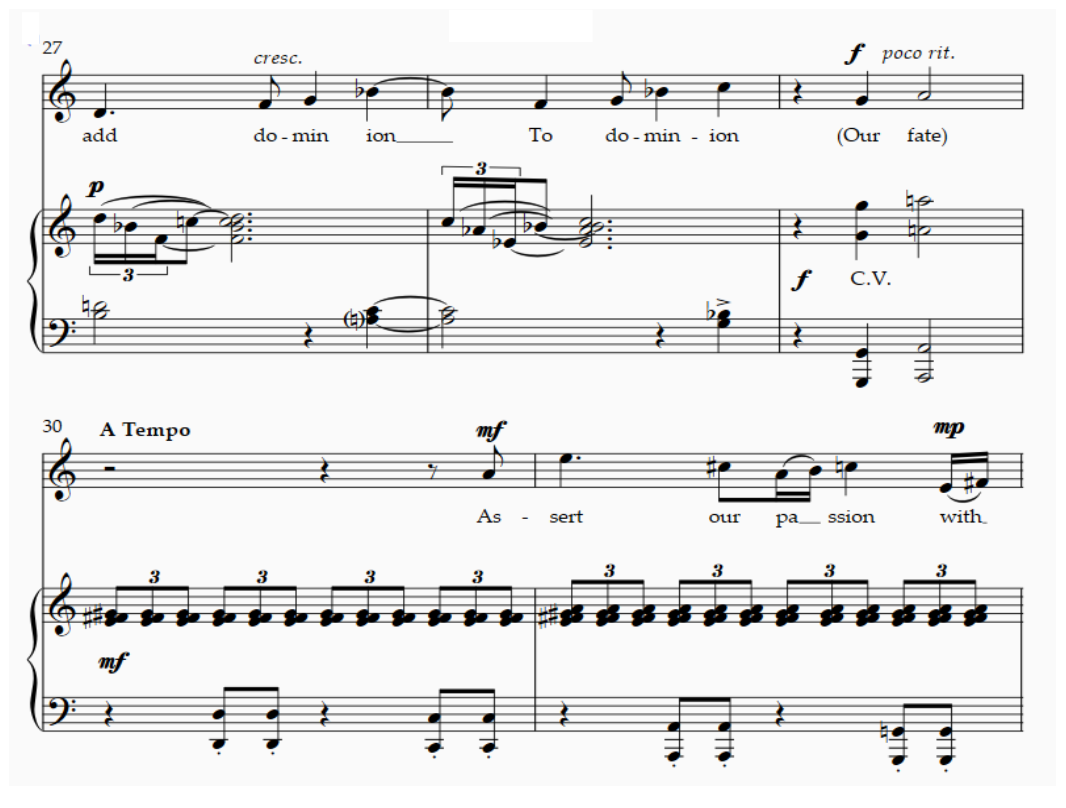

The subsequent piano motif uses quasi-improvisational flourishes in the right hand, complementing the vocal line extremely effectively. On the lyrics "Our fate", the piano is in unison with the voice and leads swiftly into the final section of the song, where the agitated triplet accompaniment pattern from the opening returns, unsurprisingly given the return to the atmosphere of stanza in the text at this point.

Figure 6 – Bodley, "Aflame", bars 27-31

The last line brings a reappearance of the lyrical, settled accompaniment from stanza 3 (marked Andante), again unsurprisingly, given the similarity in text – this line also recalls the idea of "roving". The final chords gradually bring the piece to a pianissimo close, thus supplementing the subdued return of the A major sonority effectively.

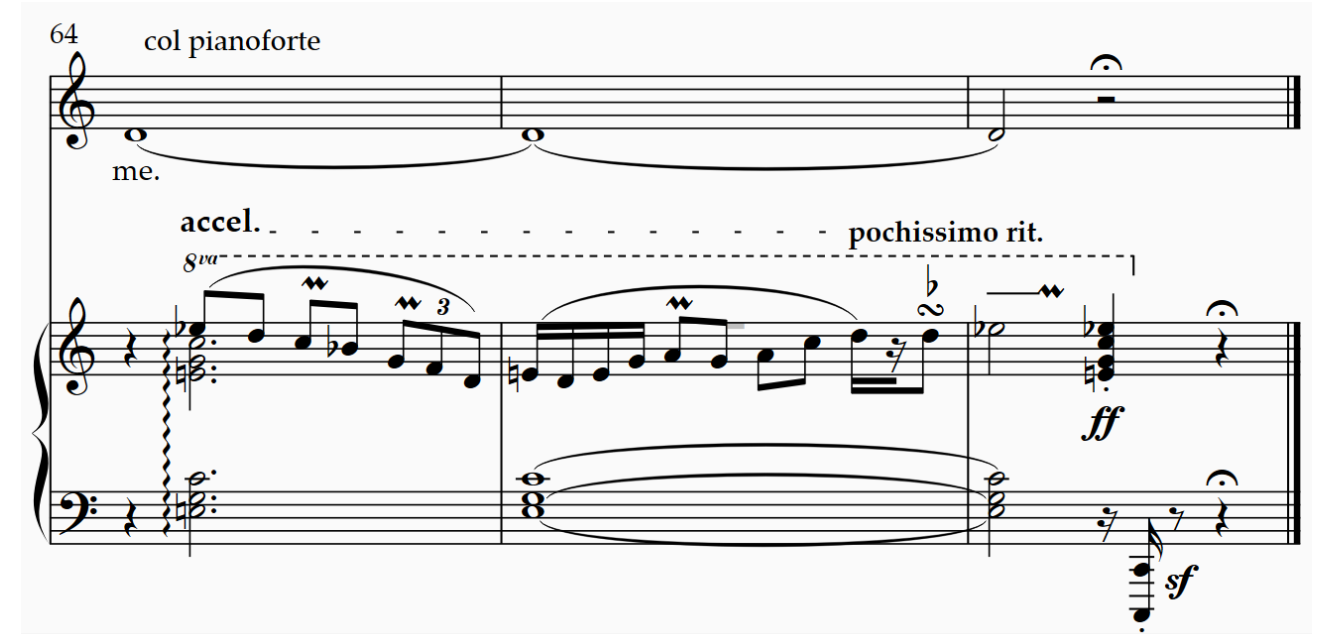

Although "Aflame" is perhaps the movement which is least indebted to Irish traditional music, there are several important elements to be pointed out: firstly, the use of the mordent at bar 37 (on "inner"), which crops up frequently in subsequent movements, especially the third, "A Human Voice", both in the piano accompaniment and in the vocal line. The final three bars of this movement embody a quasi-jazz-like ending utilizing an array of ornaments in the Irish traditional style, including mordents, extended mordents, and turns:

Figure 7 – Bodley, "A Human Voice", bars 64-67

Bodley himself indicates in the prefatory notes to the score that "the mordent always starts on the accent, never before it" (Bodley, 1985), which is typical performance practice in Irish traditional music.

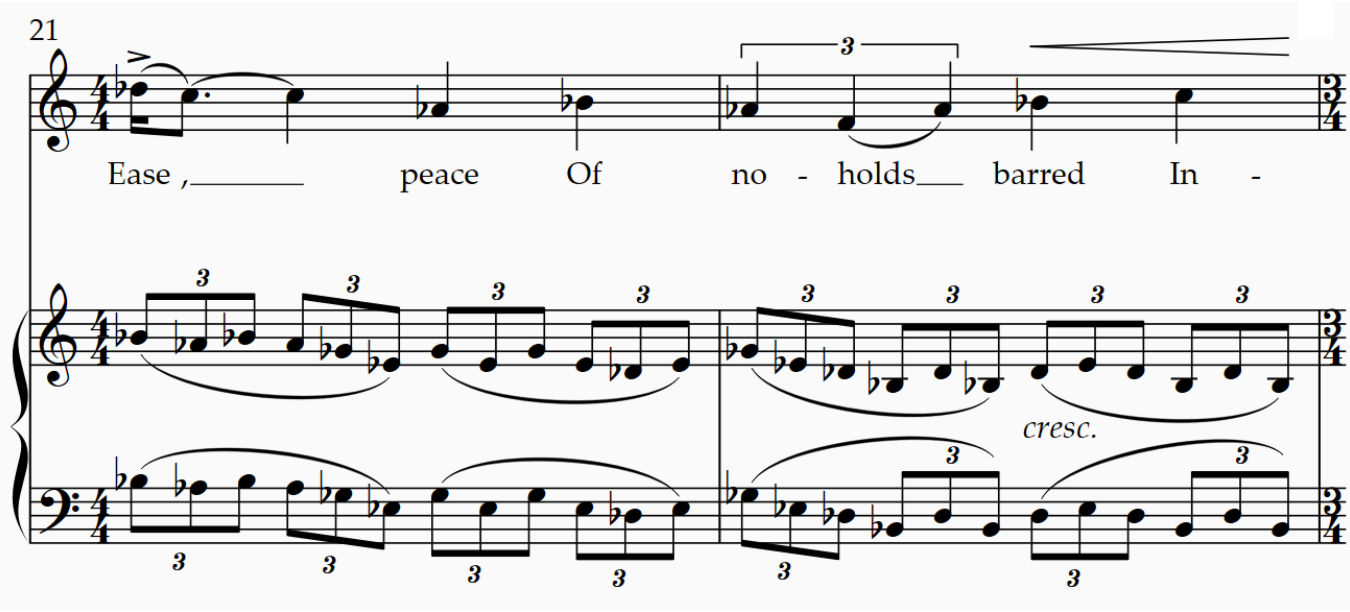

Secondly, the fiery rhythmic accompaniment evokes a sense of an Irish slip jig in 12/8, a feature which foreshadows the accompaniment writing in the middle section of the third movement:

Figure 8 – Bodley, "A Human Voice", bars 21-22

The accompaniment style of the second movement, "A Quiet Evening", is far more modernistic than explicitly Irish, and yet, its primary strength is the affordance it allows the singer to replicate the Sean-Nós style. The subdued, responsorial nature of the accompaniment patterns in this movement gives the vocal line freedom to soar above it freely, thus evoking, again, a sense of ‘Irish-ness’ in a contemporary musical setting.

Ultimately, it is Bodley’s ability to fuse two traditions so seamlessly, without neglecting one in favour of the other, that renders his writing for voice and piano so effective. And indeed, A Passionate Love is just one such example of this seamless fusion.

Bibliography

- Bodley, Seóirse, ‘Song Recital’, RTÉ, ID1237, RTE/70 (06 February 1986) [accessed 14 February 2024 at the Contemporary Music Centre]

- Bodley, Seóirse, A Passionate Love, Contemporary Music Centre (Dublin: CMC, 1985)

- Boydell, Barra,‘Recital at Lane Gallery’, The Irish Times (07 May 1986), pp. 10 [accessed 28 February 2024]

- Cox, Gareth, Seóirse Bodley (Dublin: Field Day Publications, 2010)

- Fitzgerald, Mark ‘A belated arrival: The delayed acceptance of musical modernity in Irish composition’, Irish Studies Review, 26 (2018), 347–60

- Klein, Axel ‘Bodley, Seóirse’, in Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press) [accessed 04 March 2024]