Digitising Joan Trimble's 'Intermezzo'

Elyce Brady, an MA Performance and Musicology student at Maynooth University, recently completed her digital skills placement at CMC. Her work involved the digitisation of Joan Trimble's 'Intermezzo'. The following article details Elyce's research accompanied by some of the digitised material.

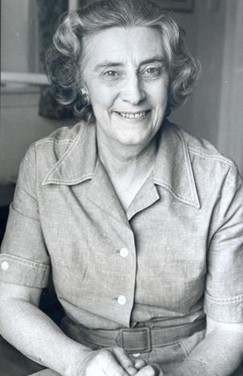

Joan Trimble (1915-2000)

Joan Trimble was a pianist, violinist and an accomplished composer. Her early compositions won prizes at the Feis Ceoil in Dublin and the Royal College of Music in London.

She was part of the successful two-piano duo, alongside her sister, Valerie Trimble, and on occasion, used her compositional skills to create four hands arrangements of famous solo piano works, such as George Gershwin’s 'Rhapsody in Blue'. Usually, Trimble’s compositions were either commissioned or upon specific request.

She did not consider herself a skilled solo pianist due to her small hands, even though she was invited to play piano for renown Irish tenor, John McCormack, on his farewell tour.

Check out the following clip from RTE Archives here to get acquainted with Trimble.

Joan and Valarie Trimble

As an Irish female classical pianist, myself, I was honoured to have the chance to delve into the legacy of Joan Trimble during my internship at the Contemporary Music Centre in Dublin. I was particularly interested in exploring the works and achievements of a prominent Irish female figure from the classical music scene, due to my own identity as a woman and Irish heritage. As a Cavan native, myself, I was intrigued to research a composer and musician from a neighbouring county.

My article will delve into Trimble’s 'Suite for Strings’, with a focus on ‘Intermezzo’, her Irish identity and career as a female composer, and my experience with the digitising process of this work. I will firstly provide an insight into Trimble’s upbringing.

Trimble was born in 1915 in Enniskillen, county Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, and grew up amidst World War I, the Civil War, and the War of Independence. Her upbringing was rooted in a musical household, as her mother was a classically trained violinist and instilled an importance of musical education in Trimble from a young age, as she was sent to Dublin, weekly, to attend violin and piano lessons at the Royal Irish Academy of Music.

Trimble studied Music at Trinity College Dublin, received her BA degree in 1936, and her BMus qualification in 1937. She then pursued further studies at the Royal College of Music, in London, in composition and piano, until 1940. Her early musical career was greatly impacted by the second World War.

As air raids disrupted concerts, the musical scene in England quickly dispersed. As a result, Trimble had to look elsewhere for work, and took on a new role as a Red Cross nurse, which was very demanding as she had shifts of 8+ hours a day in hospitals and clinics. During this period, she had very little time to compose. In 1942, she got married and soon became a mother which brought on new duties in the home and extended her lack of time for composing.

'Suite for Strings' was composed in 1951 for string orchestra, and originally comprised of four movements:

1. Prelude, 2. Intermezzo, 3. Air, and 4. Finale.

Movement 2, ‘Intermezzo’, was removed from ‘Suite for Strings’ upon Trimble’s request.

In an interview with BBC Radio Ulster [BBC Radio Ulster: Contemporary Music Centre Archives] she mentioned that ‘Suite for Strings’ reflects the lack of free time she had to compose, as she cringes in reflection of this work and considers it her worst. Her unfamiliarity with writing longer compositions led to her discomfort of one movement in particular, known as ‘Intermezzo’.

Trimble’s father encouraged her to submit an entry to a competition held by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. She didn’t want to compose a two piano piece or anything that she had done in the past, and so came about the idea of ‘Suite for Strings’. At this time, Trimble had never composed a work longer than 9 minutes, and as a result, she was runner up in the competition. She later removed ‘Intermezzo’ from ‘Suite for Strings’ as she considered the movement to be out of place in this work. Today, ‘Suite for Strings’ is performed with only Prelude, Air and Finale.

Shortly after writing ‘Suite for Strings’, Trimble retired from composing as she considered the new trends in composition to be something that she could not keep up with, and she had the firm belief that if anyone is to be successful at anything, they must dedicate themselves fully to it, [Jane O’Leary, ‘Outside the Pale of Musical Civilisation’, The Irish Composer (1988)] which she could no longer do.

Check out the following podcast that features a discussion with the Contemporary Music Centre’s former Library Coordinator, Susan Brodigan, about digitisation projects in CMC’s library which includes Joan Trimble’s ‘Suite for Strings’, (with the exclusion of ‘Intermezzo’):

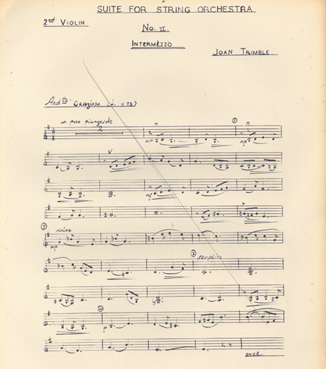

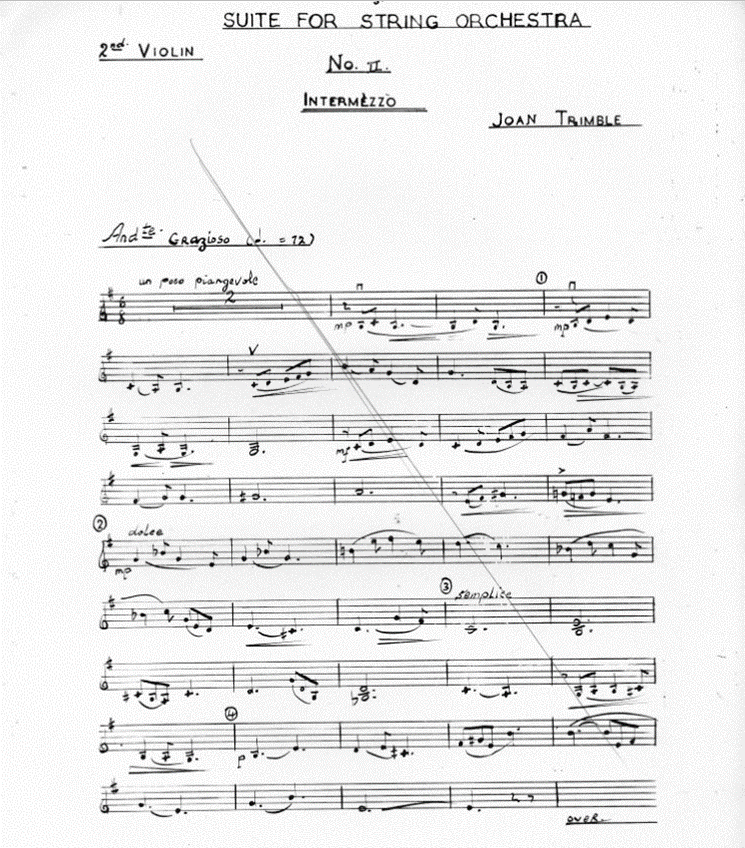

At the Contemporary Music Centre, I worked with handwritten manuscripts of ‘Intermezzo’, which had a line crossing over the notation on each page from the beginning to end, in violin 1 and 2, viola, cello, and bass.

The developments made in technology and software today, such as MuseScore or Sibelius, have enabled current composers to create works without having to spend any time physically writing manuscripts.

In a way, the digitising process immortalises the composer’s work as it lives on digitally and enables a larger audience to view it. In editing software, such as PixEdit, an old manuscript can be revived and stored digitally, however, lines and irrelevant markings cannot be removed easily. Above is a snippet from Violin 2 and the outcome of the digitising process. As you can see, the line through the notation from the top of the page to the bottom is still visible. (This line reflects Trimble’s later disproval of this movement).

Trimble’s pursuit of undergraduate studies at the Royal College of Music came about just as a major development in job opportunities for female composers occurred. During the1920s in England, 76% of music educators were female [Jennifer Doctor, ‘Intersecting Circles': A Journal of Gender and Culture, 2

(1998), pp. 90–91]. Despite this new age of opportunities for women, Trimble thought ‘composition was a man’s world’ [Trimble, ‘Joan Trimble’, p. 278]. During her musical studies, she knew very few female composers, and all her mentors were men. Therefore, a lack of women in this area meant that she had no female role models to look up to.

Despite Trimble having spent most of her career in England, she maintained a passion for her Irish heritage, culture, and music throughout her lifetime. In the words of Kevin Myers, ‘She was at home in independent Ireland; at home in Northern Ireland; at home in London. Her own commitment to Irish culture gave a special sovereignty all of her own.’ [Kevin Myers, ‘An Irishman’s Diary’, The Irish Times, 12 October 2000]

Joan Trimble’s legacy is evident at CMC as you can find many of her works archived and digitised here. Her lifelong accomplishments have been recognised by the Fermanagh Trust in the set up of the Joan Trimble Awards in 2002, which continues to encourage the participation of Ireland’s youth in creativity, the performing arts and Irish culture.

Elyce Brady, MA Performance and Musicology student at Maynooth University

This article was created in association with the Department of Music at Maynooth University. Students undertook a five week placement as part of their MA course and gained experience in research, digitisation, and web publishing.