MU student Rebecca McCabe writes about Evangelia Rigaki’s 2019 opera This Hostel Life

Rebecca McCabe is a MU Masters student in Musicology, where she is undertaking a four-week placement with CMC. Her research is based on composer Evangelia Rigaki’s installation opera This Hostel Life, which represents life in direct provision in Ireland. Throughout her years of academic research, Rebecca found interest in social issues that are represented through music. After thoroughly researching gender and sexuality in music, she was eager to get started on migration issues, that Rigaki portrays in her musical works.

Composed in 2019, This Hostel Life shows different perspectives of life in direct provision. There are approximately 7,400 adults and children living in direct provision centres across seventeen counties in Ireland, as of August 2020. Each adult receives a sum of €38.80 weekly, with an extra €29.80 per child. Human rights activists across Ireland have been fighting for a better system to be put in place for those seeking asylum. It’s the hysterical distress of this lifestyle that Rigaki represents through her unique installation opera, This Hostel Life. I was fortunate enough to get the opportunity to interview Rigaki about the compositional process, and also James Bingham, who produced this opera for Irish National Opera. Without the help of Susan Brodigan and Keith Fennell in CMC, I would not have had the opportunity to speak with Rigaki and Bingham, and also get all the digitised materials used in this article.

Author Melatu Uche Okorie with composer Evangelia Rigaki. Photo: Kip Carroll, source Irish National Opera

It’s interesting to note that this opera isn’t the first of Rigaki’s to challenge social issues. Her 2014 composition The Pregnant Box, is a portrayal of women concealing pregnancies in a Catholic Ireland. The juxtaposition between unwanted pregnancies and religion caused Rigaki backlash and even some threats. Nevertheless, it was an important issue that needed to be spoken about, and after engaging with clergy, it was decided that the music was not offensive or sacrilegious. With a combination of passion for social issues, and a commission from Irish National Opera, Rigaki completed This Hostel Life in late 2019. Rigaki based her opera on the book written by Melatu Uche Okorie, which features the same title. Okorie’s book consists of three stories, one of which is based on her own experiences after moving to Ireland from Nigeria, and living in direct provision for eight and a half years. Every piece of libretto in This Hostel Life comes directly from Okorie’s book. The text shows the raw emotion that Okorie has towards direct provision.

This hostel has changed drastically in recent times and everyone has turned a blind eye to it…Direct provision is like being in an abusive relationship.

The ways in which Rigaki went about representing the emotion of the text through her music was with strategic and extended techniques. She composed for two sopranos, Amy Ní Fhearraigh and Rachel Croash, as well as one tenor, Andrew Gavin, and a choir. Each singer performed separate pieces with musical accompaniment from one instrument. These accompaniments included flautist Bill Dowdall, percussionist Richard O’Donnell, and bass clarinettist Finton Sutton. The extended techniques in the pieces were composed in collaboration with the singers, after multiple workshops, so Rigaki could compose music that would complement their abilities. The opera itself is divided into four ‘encounters’, like Okorie’s book - The Egg Broke, Under the Awning, Third Encounter, and This Hostel Life.

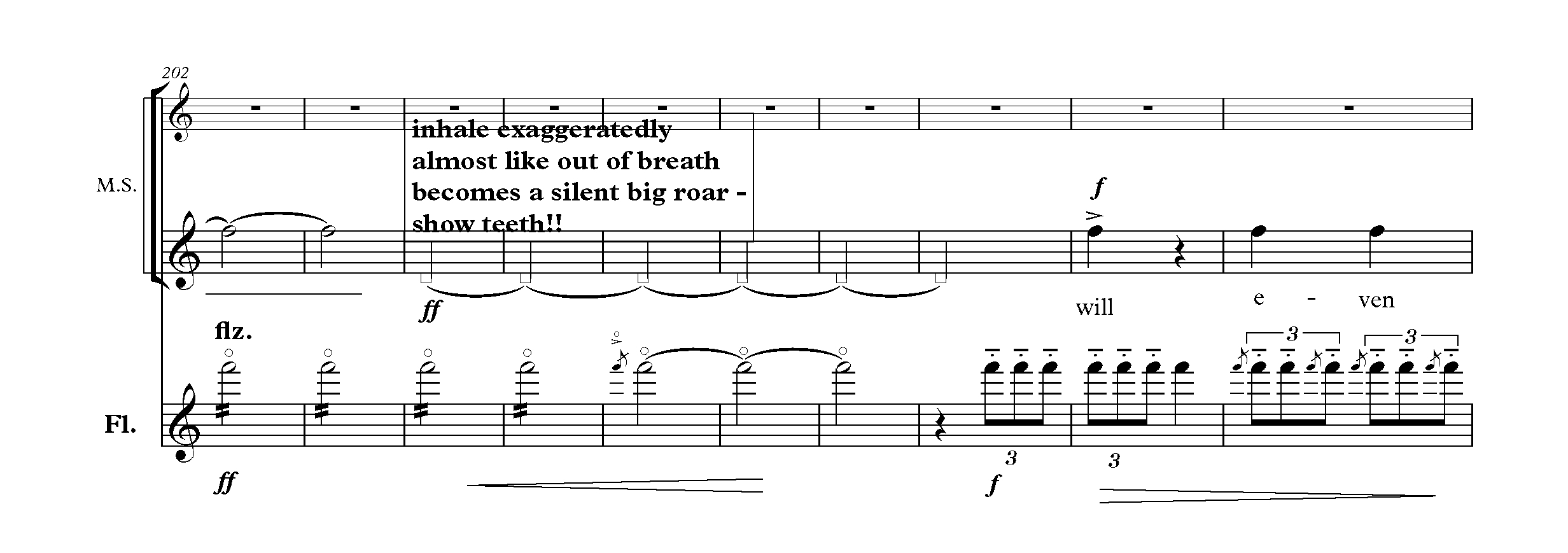

Each encounter displays contrasting moods and emotions by the singers. For example, the opening piece in the first encounter is almost like a lullaby, while the singer is performing different variations of the sentence ‘I love being a part of this family.’ However, things take a sinister turn in the next piece. The same soprano and flute combination perform rhythmic variations of the sentence, ‘most women in my shoes would have been threatened by their husband’s family.’ Unlike the previous piece, the singer is emotionless and we can even hear the pain in her voice. This concept of contrasting timbres is used throughout each encounter. Some of the extended techniques that Rigaki uses include the singers whispering, gasping, and even silent screaming/gagging at times. Engagement with the audience was also an important aspect to the performance. Throughout the score, performers are indicated to interact with them in different ways, whether it's conversational style singing, or expressing pain.

Bars 202-211 in the score for the third encounter, The Egg Broke.

For certain parts of the opera, singers are instructed to use everyday objects as instruments, such as water. In the first movement of the second encounter, ‘Under the Awning’, the water the singer plays with is in connection to the text. “Back home rainful meant other things to you, rather than discomfort. It meant that the flat you shared with your mother’s sister and her husband and your three cousins would not be stuffy.” Performers are instructed to lift water and let it drop back into the bowl, and to also wash their hands vigorously.

Bars 119-125 in the score for the second encounter, Under The Awning.

One of the most interesting aspects of this opera is the way in which it was performed. Rigaki and Bingham said themselves that listening to the pieces, without experiencing the performance, do not do it any justice. It was the experience of physically being at the performances that made it so unique. Both performances, which were on the 26th and the 28th of September 2019, were located in the crypts of the Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. When asking Rigaki about the venue in our interview, she described it as "very risky". Leading up to the premiere, musicians rehearsed in a separate venue, so their first time performing in the crypt was the night of the premiere. Each singer was paired with one instrumentalist and located in separate rooms of the crypt. This meant that because each piece was being performed simultaneously, when audience members entered the crypt, it was up to themselves to follow whichever piece of music interested them. Therefore, each person had their own individual experience of the opera. The architecture of the crypt with its thick walls and low ceilings provided different physical perceptions of sound. Rigaki stated that to her, ‘it was parallel to what someone might experience in a direct provision centre.’ It wasn’t exactly a spacious venue, but that’s what added to the experience and what the opera represents.

James Bingham, the producer of This Hostel Life, spoke with me in regards to the structure and organising of the performance.

We said to audience members the pieces are open from now, so you can come at any time and leave at any time.

Crowd control was a factor that needed to be considered carefully. However, living in direct provision was not only represented through the music, but it was also represented through the venue. In a way, having the audience in a small, almost claustrophobic venue, heightened the illusion. So having ushers to guide audience members around the crypt would break that. However, there had to be some form of crowd control, to prevent the audience from staying in one room. To do this, they organised the movements to be performed at different times, in different combinations.

Behind the scenes photo of the premiere in Christ Church Cathedral, provided by Evangelia Rigaki.

After two nights of the opera being performed, Rigaki received excellent feedback. The idea of giving the audience a unique and intimate experience was a success. As well as this, regular opera attendees gained insight into the issue of direct provision in Ireland. Irish National Opera also issued tickets to people living in these centres, so they could join in on the experience. Tickets to attend for both nights, sold out completely. This was not a traditional opera performance. The intimacy of the venue and the nature of Rigaki’s compositions gave the audience their own individual experience. All in all, Rigaki successfully represented an issue as important as the direct provision crisis in Ireland, through her wonderful music.